by Fitz | Aug 2, 2014 | Journal

Foreward

Thanks for taking a look at this “work in progress. It originally started out as an experimental one-man play. Maybe it still will be. Later I thought of making it into a novel, but it’s hard to see it happening as there is (intentionally) no real plot, and whenever I tried to make a traditional plot, my original vision began to fall apart.

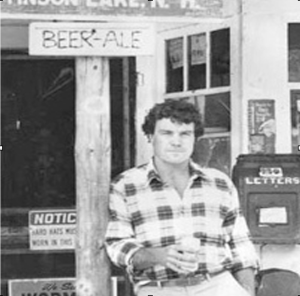

The idea for the story (as opposed to having a plot) is to capture the truth about a certain place in a certain place in time. There is no antagonist aside from the cruel and unrelenting vagaries of fate. The characters deal with the common struggle to forge an identity and shape their lives as best they can. The common thread in all of there lives is the voice of a narrator–a voice who simply retells the sketches and scenes from the community that lives on Hallow’s Lake–a place loosely based on Stinson Lake in New Hampshire–which was so pivotal in my life as I grew up, and even after I “grew up.” The narrator is a young man who simply helps people out and, in a sense, is simply there to record the words, actions, and interactions of the characters.

If there is any strength in the writing, I think is in the sketches of ordinary people with ordinary demons consciously and unconsciously helping each other survive in a somewhat isolated community. Nobody’s life is anywhere near perfect and in the unfolding of the scenes, I am trying to imply that each character’s life is incredibly complex, deeply emotional, and surprisingly intellectual–with the implication being that there is no such thing as a minor character in life.

My big issue is–and has been–how to wrap up a story that does not have a linear plot or an easy to recognize conflict around which to focus my readers. My most recent thought is to simply call it poem, not a story–which would solve a lot of my uneasiness surrounding how to “release” this piece. In many ways, it is similar to Dylan Thomas’s approach to writing “A Child’s Christmas in Wales,” though he at least had an abiding and enduring theme around which to hang the images, actions, and memories of a child’s Christmas–his Christmas, perhaps.

I will keep adding to this as time allows. As it stands now, I have sketches for at least twenty chapters.

Any thoughts or ideas are appreciated. I have a pretty thick skin about my writing, so please be as bunt as you need to be.

And thanks,

Fitz

8/25/2014

Chapter 1

The Store

I hung my sign outside and came in. But there’s no one here. [ Maybe return to this in the end as it starts out in the present tense.]Not Fred or Sally, or Mary, who is usually here on Monday mornings. Next to the register are three five dollar scratch tickets, a can of Franco and a loaf of bread. I’m sure Josh came in and spent his money on scratch tickets and then couldn’t afford the bread and Franco. I’ve heard it a million times: “No Credit, no way, not for you.” Strange that Fred won’t let Josh have a can of Franco for a dollar and forty-nine, but he will pour him a styrofoam cup full of Canadian Club every afternoon. That must cost Fred at least a dollar and forty-nine. Josh loves Franco. Especially cold, he says, on stale bread. And Canadian Club.

When no one is here, I tidy up the store. Sometimes I do when people are here. Mary is the only one that helps me. But she is only here three days a week. I always dust the cans and jars on the shelf, and I make sure everything is by the alphabet. Before the outside mail comes in, I separate the mail into New Hampshire addresses and out-of-state addresses. Mostly, it’s New Hampshire addresses, except for the summer families and Robere. Robere sends mail everywhere. He’s a writer, so it mustn’t be so hard to write so many letters. When Fred gets drunk in the afternoon, sometimes he yells and says “don’t dust the pickles so much that people can read the sell-by date.” Then he laughs and puts his cigar back in his mouth and blows three clouds of smoke in my direction. It always seems like three, but I don’t always count. Usually I do. He won’t if Sally is downstairs. Fred is like that. Most guys are. Except Owen.

There are always cases of beer on the pool table. Nobody plays pool during the day, except for summer kids. Fred says, “If the little Einsteins want to play, let them put the beer in the cooler.” They usually do. I fix it all later. Schlitz on the top shelf. Budweiser on the bottom. Most people drink Budweiser. Trapper gets a Narragansett and a Slim Jim everyday. He gets a Narragansett first because the cooler is near the door, then he walks by the candy bins and grabs a Slim Jim. Then he sits in the chair by the stove. He opens the beer and says “First things first.”

Magdalene came in one day with three kids from the Baptist camp. One of the kids asked her why he always got a Slim Jim and a Narragansett everyday. Magdalene said to ask Trapper. She did, and Trapper kinda’ snapped, “Because I’m f___ing different. That’s why.” The Baptist kid started to cry, and Magdalene just said, “See,” and shook her head at all of us. Josh said, “Well, you asked.” Fred said, “Go home Trapper.” He did, but he came back in and said he was sorry to the girl. Then he grabbed his Narragansett, “I paid for it, so I can’t be that much different.”

A little while later we could hear him yelling “f___” from somewhere down the road. Every time he yelled, it echoed three times. He was probably on the point near Maggie Johnson’s place. Maggie’s point is the best place for an an echo. And it’s best in late fall. Magdalene and the Baptist kids walked the other way around the lake. The paved road is just a bit shorter, so it wasn’t much different to go that way. But you can’t ever see the lake from the dirt road. Though you can from the upper field of the reform camp. I don’t think the Baptists do anything with the reform camp. Robere said if Trapper was shouting “f___” by Maggie’s house, it was probably a question. Josh liked that one: “F___?” “F___?” He looked at all of us with his head cocked sideways and his lips stuck out and said that about twenty times. Robere said, “In your case it isn’t a question; it’s a plea.” Even Sally laughed at that one. Robere always has a comeback. He’s quick that way.

We heard Jake’s air horn and the air brakes locking up across the street. He took his green Poulan cap off when he walked in. He always takes his hat off when he goes inside anywhere. He laughed and smiled and grabbed a Budweiser. “Hello all: Neil, Josh, Sally, Fred, and a special hello to the cunning Frenchman.” Jake always says hi to everyone in the store. If he doesn’t know the people, he just calls them summer person one and summer person two, or person trying to find what will never be found in this store, or mad snow-mobiler with sore ass. Most people seem to like the attention. Some don’t. When those people leave he says, “Goodbye, you sorry ass pedant.” Robere taught him that word. For all we know, Jake’s the only person in the world who says it. He really loves that word.

Jake said he saw Trapper standing on Maggie’s Point, “So I give him a blast, and then he gives me the finger. Some kind of grateful, eh? Or else he thought I was Roy.” Robere opened a bottle of wine and said, “He’s just ready to take on the world.”

“Or Maggie,” said Fred. Everyone laughed. Even Jake who just got there.

Sally kicked us out when Josh tried to take off his cap with a drink in his hand. Robere said, “That’s one way to kill lice.” Josh smiled at him and said, “F___?”

“After I walk you home, you sorry bastard.”

At one point or another, everyone helps Josh home.

My house is Kathryn Elizabeth’s house. It’s on the cove on the west side of Hallows on the lake side of the road, and there isn’t an echo like Maggie’s. It is just a five-minute walk to the store.

Chapter 2

Kathryn Elizabeth

When I come home, Kathryn Elizabeth is almost always playing cards in the nook that looks over the dock. She leaves the window open a crack and smokes Pall Mall cigarettes. She arranges the butts in the ash tray in a circle. With all the red lipstick it looks like a rose. “The only rose I’ll ever get.” She said that once. I told Owen and he gave me a rose to bring home. “There’s at least one damn saint in the world.” She smiled when she said that. I smiled back. Owen does things for people. At six o’clock she pours herself a whiskey and watches TV. At 7:30 she goes to bed. Sometimes 8:30 in the summer. But it’s one or the other. Every night I throw away the ashtray rose. She makes a new one everyday. She kept Owen’s rose in a glass on the mantle. After a long spell the rose dried to a brittle brown. She stood there one night and grabbed her chest and held the mantle with her other hand. S___, she said. “kill me twice, why don’t you.”

It’s the only time she ever swore. I don’t think she remembered that one swear. So much else went on.

When I was in school she would say, “If you let the fools get you down, you ain’t never gonna get up.” I knew what she meant, so I smiled at her. Even when it hurt, I smiled at her. Jake beat up a village kid who said something to me once. I shook my head and didn’t smile. He sat with me on the bus ride home. He told me it wasn’t a big deal. But it was good enough reason to beat somebody up. And who better to beat up than one of the village kids.

After Kathryn Elizabeth goes to bed, I throw away her ashtray rose and clean up a bit. I shuffle her cards and put out a new pack of Pall Malls on the table, and a bowl and a box of Special K. Sometimes I have to go back to the store for cigarettes or milk. Sally is good about making sure there is Special K. I put it next to the Rice Krispies because Sally says they are really for Kathryn Elizabeth. Some of the summer folks eat them, too. Most of the year it’s just for Kathryn. So it makes sense to put them next to the Rice Krispies. Krispies and Kathryn are close together. And so is special and rice. So it still makes a lot of sense.

She gets up at 4:30. “If I don’t help the sun rise, it ain’t gonna rise. That’s the only truth I know, Neil—it’s the only truth I know.” She closes her eyes when she hears a logging truck go by. Sometimes she says a hail mary while holding down the top of my hand. Jake says he’d go around the back side of the lake if he could, but most of the year the shoulder is too soft. He rolled his rig once on the back side of the lake. But it was empty. So he stayed alive. With a load of pine you might live.

Oak is what kills you—it always kills you.

We drink coffee in the morning and watch the sun rise over Batemen’s cliffs. Kathryn Elizabeth smokes and drinks and eats the same way each time. A pattern she follows. Once while looking at the lake, she said, “It’s a beautiful mirror, Neil, but only a fool puts it on the wall.” Sometimes in the black and white morning there’s a fisherman trolling for lake trout. He looks like a dark paper cutout that doesn’t move. Only the lake moves—sliding underneath a dark rowboat like it’s still carrying the dream of the night. Dreams, memories and shadows.

Robere said that, “Nothing is real until it is put into words. It is simply dreams, memories and shadows. I used to wonder why someone would fish all night. I don’t, now.

On a good day in the summer, the sun burns itself slowly into the lake and weaves a few strands of red clouds around it. The clouds belong to the sun. It creeps into the lake off the beach of the reform camp. First there is a sliver of light, like when the moon is holding water, then a half sun, and then the lake captures the whole sun itself and holds it until it reaches the bog. Then it is lost in a puzzle of driftwood cedars, hummocks and lily pads. It traces the outline of Cribbers Mountain for most of the rest of the day. When I get the feeling, I watch the sun set from Batemen’s cliffs. In the summer, the lake houses go on like popcorn and it’s hard to tell. In the winter it’s slow and predictable. I almost always get it right.

Jake says we are the children of the light because we see the sun first. Robere says the east side of Hallows has the true children because they see it last. Josh was drunk and said, “We live in a god forsaken f___ing salad bowl and none of us sees it first or last. Sally said, “Where you stand depends on where you sit.” Trapper said “Great, we’re all right, just like the rest of the G__damned world.” I think Robere is right. In the winter we are swallowed so early by the cold shadow dropping off Kittewauk Mountain. “They’re the ones smiling now, Neil.” That’s what Kathryn Elizabeth says when she has her whiskey and the cold is crawling in and she sees the east side of Hallows bright and singing in the sunset.

Only the moon treats us the same. Jake says the moon is stolen light. Jake’s father was a Penobscot. He never said anything anyone could argue with. He died in a night with a blue moon. Kathryn Elizabeth sat with Jake’s mother for three days and gave her the rosary beads that used to hang on the pineapple bedpost. “It’s time, Neil,” she said, “to pray in a different way.”

Chapter 3

Mary

Not long after Thanksgiving Mary came. She just showed up at the store looking for a place to work and a place to live. Fred pointed to everyone in the store and said he couldn’t feed a tank of gerbils with the money he makes from these characters. Even Trapper was polite and said that Kittewauke Mountain was looking for chairlift attendants. All you have to do is say, “Next,” pull down the bar, slap the back of the chair and say “next” again. “It’s a piss of a way to spend the winter.” Robere said, “Don’t mind him. Even when he doesn’t try, he says something stupid.” Fred said, “Wish we could help.” She said, “Thank you” and left. I held the door for her. She smiled again. I can’t remember if I smiled. She seemed beautiful. After she drove away, Trapper said, “f___?” and took a bite of his slim jim. Fred blew smoke at Trapper and shook his head.

The next Monday, Mary was in the store putting magazines in the rack. I hung up my sign and went to help her. But she was holding the magazines in plastic wraps. She smiled and rolled her eyes. My face felt hot and I tried to smile. I walked over to the cooler. There was some Budweiser on top. Josh came in and said, “Well, hey Mary, Fred must have got rid of his gerbils.” Fred walked in with an armload of wood. “I did say, ‘I wish we could help,’ didn’t I? Mary is from Wyoming, so I imagine she can make it through one of our winters.” Josh said, “But can she make it through you?” Sally was right behind Fred with a bag of snowmobile mitts. She set it down next to Mary and said, “I’ll teach her the art of dealing with the local peasantry.”

Josh put a can of Franco and a loaf of bread on the counter. Mary rang it in. Josh left and said, “You’ll see this pissant at sundown. Pissant. Eloise used that word once in scrabble. She had a million of them words. Half the time I didn’t believe her.”

Outside the snow was already piled so high that the phone booth was surrounded on three sides. It snowed 30 inches on November 19. The village got less than a foot and then all rain. It snowed again on Thanksgiving. And then again a week later on December 3. The icicles on the porch were so clear you could still read the ‘Worms and Crawlers’ sign on the front window. I tried to read my sign. I couldn’t, but I knew it said: ‘I will help you with your work. Ask inside’. Fred or Sally tell me who to help. Most of the time in the winter I work with Jake. I broke the icicles off and swept the porch. Fred wants me to. “All I need is to be sued by some New Yorker with a busted noggin.” Fred said that once.

Later I heard Sally tell Robere that Owen came across Mary’s car stuck in a bank by Sawmill Road. He winched her out and talked to Fred. Fred told Mary she could work three days a week and live in the apartment behind the store. Diggy had been living there. One night Fred brought up a marijuana bong made out of pvc pipe and radiator hose and said, “At least he learned something at that tech school.” Jake laughed and told him he could probably sell it to Ethan and Aaron. Ethan and Aaron are twins. They live off the grid on twenty-five acres on the back road to 93 by Tarbell Springs. Josh says, “You got to hand it to them; they’re damn handy.” Trapper said, “More like Randy. They ain’t f___ing twins.”

*****

Diggy and Jenny are twins. Diggy acts almost normal with Jenny around. Jake’s father said real twins don’t need words to communicate. That god does it for them. Jenny went off to school in Pennsylvania. She comes home for Christmas, and then again in mud season. One night, when they arrested Diggy for selling oxy, Sally was crying. Trapper said, “At least you got one ying for your yang.” Only Magdalene, Sally and Owen visited Diggy in prison. And of course, Jennie in mud season. Fred said they should just send him to live at the reform camp in a tent with the twelve-year olds. Because that’s how he acts. He spent six months in prison. But he didn’t change much.

*****

I helped Mary and Sally clean out Diggy’s apartment. It is just three rooms added on to the back of the store. A big room with a woodstove and a kitchen, a bathroom, and a small bedroom. Though it has a nice deck with a slider that looks over the gas pumps on the dock south towards the dam. I helped Josh for a week to build it. Josh built it in exchange for what he owed Fred. It smelled like old clothes, stale beer, marijuana and cigarettes. Sometimes Sally stopped and held something of Diggy’s in her hand. Mary kept saying, “This doesn’t feel right.” Finally Sally set her down on the bed and held both her hands and said, “Mary, it’s right.” When Diggy was home he could sleep in his room above the store.

Everyone loved Mary. And everyone loved the baby. A boy born on Christmas day. “Holy Mary, mother of Jesus.” That’s what Trapper said every time he came in to the store and Mary was there. But she named the baby Mathew, because Mathew is a gentle name. Jake made Mathew a rocking crib that looked like a rowboat. Fred moved the chair next to the cooler and set the crib by the stove. Fred put a fan by the griddle vent. He’d hold his smoke in, then lean back on his stool and blow into the fan. “See,” he said to Sally, “I can change.”

Chapter 4

Robere

Before and after the ice, when I walk home, I can hear Robere’s skiff. On choppy nights, above the overworked whine of his small outboard, the waves bang against the aluminum and the oars bounce on top of the seats. Josh told him he should play a tuba, then he could really sound like the school’s marching band. He reaches his dock across the lake about the same time I get to Kathryn Elizabeths. On a still summer night you can hear him cut the engine and bang into his dock. The dock is aluminum, too. He has two big Newfoundland dogs. When they go out on the docks to meet him you can hear them scraping and scratching on the metal deck and barking with a muffled bark–almost like a moaning, and you can hear Robere shouting: “Thor, Molly, off the dock.” Sometimes, in the summer the Carrols are at the lake and you can hear Mr, Carroll say, “Go help Robere.” And the four kids will run on to the dock, too. Timmy and Jesse only want to play with the dogs. But Brian and Olivia will hold Robere’s boat for him. Sometimes Robere says things like, “Odysseus returns to his beloved Ithaca.” He thinks it’s funny because the Carrolls are from a town called Ithaca. On some nights he will sit with the Carrolls in their screened-in porch. His accent carries across the lake.

If it’s a windy, moonless night, I lose the sound of his skiff before I am halfway home. I run to Kathryn Elizabeth’s dock and watch until I see his porchlight. If there is rain or fog I say a prayer. And then I go in to see Kathryn Elizabeth. Sometimes she is already in bed. Then she leaves me a note. Robere’s house has a spotlight that points towards the cove and the docks of the store. The Carroll’s cottage is tucked behind some white pines. Robere’s house looks strange next to the gentle glow of the Carrolls. They use kerosene lanterns for light and an old gas stove for cooking. A big screened porch wraps around three sides of the house. On some nights I hear the kids laughing and playing flashlight tag. They always say “Hi Neil” when they see me and ask me to look at something they caught or found. Mrs. Carroll says, “Give the man some space.” But I don’t need it. They love Robere. Not everybody loves Robere.

Robere moved to the lake three years ago and bought the old Wymack place. It sits on a small point of land. Mr. Wymack built a light house on the point after his wife died. It’s only fifteen feet high and eight foot around. But Robere sits up there and writes books. Robere calls it a tower and not a lighthouse. The spotlight is on top, in a glass cupola. Josh promised to shingle the sides of the tower if he put him in one of his books. Robere said there’s a little bit of Josh in everything he writes. Josh said, “Fine, so I’ll only shingle a little bit of your tower.” But he hasn’t, yet. Robere says he was married once, and there is a picture of a pretty girl on a motor scooter on his desk.In a city somewhere. You can see the whole lake from his desk and Kittewauke wrapping around the north and west side. Batemen’s Cliffs are directly behind. It’s a bit of a walk down the tote road to get there. In the summer the bat’s fly out of the caves at dusk and swoop and dance around three ponds. I go there sometimes, when I get the feeling.

Robere hires me to help him around his place. Jake drops off extra cordwood when he can. I saw it to length with his chainsaw and split it for Robere. He says he works better when he hears me splitting the wood by hand. So I do. I usually split the wood in winter, so it will dry over the summer. I stack it near the tower and next to his porch. The tower has a small potbelly behind the desk. I cut that wood ten inches and split it finer. The house has a big soapstone. It can take twenty-two inch bolts. Out west the split wood is called bolts, Jake says. Robere calls the big ones “all-nighters.” Only oak or elm really last all night. White oak especially. Elm just smolders without giving much heat. Jake gives him mostly silver maple, but Robere thinks all maple is rock maple. So Jake smiles and says, “See, hard as a rock,” whenever he drops off a load. In the winter it’s easy to tell how many people are at the lake houses just by counting the threads of smoke. The most I ever counted from Robere’s tower was thirteen, plus the bob houses. In the summer I count the different glows. Robere will look for the longest time. “I can see everything,” he says, “At least this is a universe I might someday comprehend.”

Sometimes, Robere will burn books in his stove. He will look at me with tired eyes and say, “It is the right place for this book.” He leaves the door open and pokes the pages apart with an iron rod until the book is gone. Then he will put in more rock maple. There are wooden rocking chairs on either side of the stove. He says, “Sit, Neil, and listen.”

So I look towards Kittewauke and listen:

Chapter 5

Trapper

Trapper’s real name is John McQuilkin. His first time in the store, Owen said, “Hi Trapper,” and because John McQuilkin said, “Hello to you, you old prophet,” the name stuck. Owen smiled, and said he just smelled the oil Trapper douses on beaver and muskrat traps, so he figured John McQuilkin was a trapper. Trapper lives in an Prowler camper he got for nothing from Fred. Some summer person left to at the store and never came back. “Two years and it’s mine,” Fred said. Jake hauled it up the tote road half-up to Three Ponds where Trapper has two acres of landlocked woods. Trapper said he bought it for a song, and so Josh started singing, “Oh the cuckoo, he’s a pretty bird…” Fred got a kick out of that. Eloise knew all the old songs, so it figures that Josh has heard them all.

The camper is twenty feet long and has a small Onan generator that runs propane for electricity, cooking, and heating. It’s a struggle for him to haul the tanks to Fred for fill-ups, so he doesn’t use the generator too much. Sometimes Jake will help him with the tanks if he’s cutting up there. The trailer has a fifteen foot awning with a screened porch. In May and June the black flies would pester him crazy otherwise. I helped him one day lay eight inches of rolled insulation on the roof that we covered with a blue tarp. It helps a bit in winter. Though a foot of snow does the same. Trapper bought an old barracks style green house frame from Owen and covered that with a tarp, too. Trapper calls it his workshop, though he doesn’t seem to do much work. Most of the year he gets his water from a small stream that flows out of Three Ponds. Owen said, “Boil the Sam Hill out of the water before you drink it.” He didn’t once. He slept in a cot in Jennie’s room for a week.

In the Blizzard of ’92 Trapper almost died. His camper is only a mile up the tote road, but still he was alone for five days. Jake hauled him back to the store in the skidder and laid him on the floor by the stove. “F___,” Trapper said, more times than ever and then sat up and said, “Thank you, Jake,” and grabbed a Narragansett and from the cooler and a Slim Jim from the rack. He stayed with Mary for three days. After that, he loaded a cooler and strapped it to Diggy’s toboggan and headed off into a clear night on a full moon. “Try leaving me alone,” he said. It’s worked before.”

He came back two weeks later and never mentioned almost dying again.

*****

Since then, I walk to his camper every Thursday morning and bring him a letter from Robere. Fred reminds me to go. Sometimes Mary comes with me. Sometimes Josh goes too and says, “Off to see the f___ing young man of the mountain.” Sometimes Kathryn Elizabeth reminds me, too, but she doesn’t need to. Fred will shove a few Slim Jims and a pack of Swisher Sweet cigars in my pocket. Sally usually puts some Kraft’s macaroni packages and Folger’s coffee in a small pack, and I take that, too. And a big handful of Sweet and Low packets. One day Magdalene asked if she could help. Josh told her “Trapper was born to be helped and ye’ have been called to serve.” Owen tells me to bring Trapper a song:

“Gonna build me a log cabin

on a mountain so high,

So I can see Willy,

as she goes walking by…”

“Food for the soul, Baptist girl, food for the soul.” And he sat and closed his eyes and whistled the tune.

“Her name is Magdalene[ Should I change her name back to Magdalene just for this scene.], Josh,” Mary said.

“Not to be confused with Maggie,” Josh said, smiling with his eyes wide.

*****

One day me and Magdalene met Aaron and Ethan coming down the tote road. They’re twins, too, but not like Diggy and Jenny.

“He ain’t a quick study,” Aaron said, “but he’s a-learnin.” Ethan smiled and tipped his hat to Magdalene and said. “It’s a fine day Baptist Girl.

Magdalene smiled back and said, “Nice gun.”

Ethan said, “Well, thank you warden.” Ethan has three guns. That day he had his shotgun. A 1968 Mossberg. He bought it new in Costa Rica. There is a warden who comes to the lake. Usually he checks to see if the summer folk have a license for their boats. He has a rope that is twelve feet long and he measures people’s boats. If the boat is longer than the rope, it needs a license plate. The state makes a lot of money that way. My skiff has a license.

Fred says many times: “He’s nothing but a pain in the f___ing ass.” People buy licenses at the store, but Fred still doesn’t like him.

When we got to the camper, Trapper was hanging meat over a smoky fire. We smelled the smoke a good way off. “My neighbors, the Jeremiah Johnson’s, were just here,” he said, “figuring to teach a city boy how to make his own Slim Jims.” Magdalene sat on a stump away from the smoke. Trapper said, “Sit over here Baptism Girl. It will preserve your beauty for more than a year. So says Aaron.”

I gave him the Slim Jims and cigars. He unwrapped both and lit the cigar and waved the Slim Jim in the air. “Now, a Slim Jim, however, will last forever,” he said.

The Onan generator was running beside the camper. It had been broken since the spring. Ethan fixed it. He also fixed the fridge. “I’m ready now for Armageddon,” Trapper said, and blew smoke into more smoke and ate a Slim Jim. “And, yes, Baptist Girl, I am happy. I’m a happy, happy f___er living in f___ing paradise.

Magdalene smiled again and said, “Yes you are Trapper. Yes you are.”

There wasn’t much to do that day. I filled the cistern with still water from the brook. The twins had split the pile of wood I cut last week and stacked it in a round. It looked like a small silo. The twins say it dries faster and nothing will ever rot. Ethan taught me how to make a round pile once. Most people still like their cords stacked square. It’s easier, they think, to measure it that way.

“That’s because they’re square, too,” Ethan said.

I tightened the latch on Trapper’s door. The latch gets loose and won’t catch the jam and then the black flies and mosquitoes will get in. It’s easy to fix. Two screws, but it always seems to be loose. Trapper likes to slam the door shut.

Trapper sat on the log smoking his cigar and said, “Bye, Magdalene.”

“Goodbye, John McQuilkin,” she said.

******

Magdalene and I were back at the lake before noon. There was a state trooper cruiser in front of the store with its lights on. Diggy was sitting in the back seat with his hands behind his head and his eyes closed like he was asleep.

Jenny had made a pillow with her arms and had her head down on top of the cruiser.

Fred was talking to the trooper and shaking his head slowly from side to side. Every so often he’d blow smoke from his cigar. I could see Sally’s shadow in the window through the three clouds of smoke drifting in the air.

Kathryn Elizabeth had her arm around her shoulder. Owen stood behind them.

Chapter 6

Owen

I walked into the store. Robere was in the rocker by the stove. Owen was holding the back of the chair and rolling it softly back and forth like he was connected somehow to Robere who said, “The world is a constantly shifting puzzle that falls apart just when you think you got it figured out.” Owen said, “Or an unfolding mosaic borne every day in the rising of the sun.”

I set myself to doing what Sally would usually do. I turned on the lights in the cooler and pulled away the Saran Wrap over the meats. The steaks and hamburger meat on the left. The cold cuts in the middle and the cheeses, cole slaw and potato salad on the right. I spooned over the cole slaw and potato salad to make them look fresh. Fred always said, “If it looks fresh, it is fresh.”

Kathryn Elizabeth said, “Neil, honey, could you get me a pack of smokes?” I grabbed the Pall Malls and unwrapped that, too. Robert sat up and lit one for her and Sally. Robere sat back down and Owen passed him a Lucky Strike over his shoulder. For a long time they kept in place and swayed slowly like pendulums.

Sally said, “Damn you, Diggy. Damn you,” and put her head against the window.

Kathryn Elizabeth said, “It ain’t right that our children get taken away from us…it just isn’t right.” She said the word isn’t slowly and sad.

Sally kept her head on the window and said, “But Diggy will be back. He’ll come back. Won’t he Owen?”

“I’ll go down now and talk with Roy,” Owen said, and he’ll figure out what we need to do.”

*****

Roy will talk with Owen and sometimes with me. But no one else, really. When I help him out at his place he tells me what to do. When I leave he’ll say, “Thank you, Neil. I appreciate it. I’ll leave the money with Fred.” Usually he remembers. But not always. Sometimes when I go back he remembers that he forgot, and he’ll say, “Oh, f___, I’m sorry.” But I don’t mind.

Sometimes Owen is there, but never anyone else. One time Owen said, “Roy is helping me keep Eloise at home.” I’m not sure what Roy does, but he is from Rhode Island.

One time Roy was drunk in his chair and said, “Disbarred in forty nine states. Every f___ing state except this one, so here I am, Neil, here I f___ing am.” I brought in dry kindling and some ash that Jake dropped off. There’s a lot of ash around. Most of the trees killed by a blight. Ash reminds me of fall. Their leaves turn yellow and fall fast. Faster than any other tree.

I put a quilt around Roy and walked back to Kathryn Elizabeth’s. He never remembered that I was there.

I moved in with Owen and Eloise when I was nine. I stayed there until Eloise stopped remembering most everybody. Even Owen. One day Eloise asked why I was there. “You’re a sweet kid, aren’t you, but why are you here.”

Owen sat down with me one day on the concrete steps of the front porch. It was a hot summer day. Dandelions and witchgrass grew in the cracks. I pulled slowly at the weeds while Owen held me like a bear and kissed the back of my head, “Things change, Neil, even if it is not part of the book. Katey needs you, too.”

Owen helped me move into Kathryn Elizabeth’s house. Owen said, “Your room will always be in our house, too. That will never ever change.”

And it is.

I remember it like a china plate on an uncluttered shelf.

The cruiser pulled away with Diggy in the back. Fred walked towards the dam. He shook his head and said “F___. Goddamned f___ing shit for brains.”