by Fitz | Jul 24, 2015 | Essays, Journal

Mark Twain once wrote that it is good to be a good person, but it is better to tell people how to be good–“and a damn sight easier!” So much of my life is lived in response to the moment and not in a practiced and cultivated wisdom. I sat here this morning looking out over my backyard and penned down what should be–could be–rules I should follow to live a better life. In short, how to be more human and real.

Live with dignity:

Be wise.

Be simple.

Be honest

Be happy.

Be humble.

Be ready.

Everything else flows from this…

Show up.

Make friends.

Cook dinners.

Know your town.

Write thank you cards.

Eat healthy.

Walk places.

Pray.

Read good books.

Play an instrument.

Keep a journal.

Know bad habits.

Know good habits.

Live within your means.

Pay your bills.

Help people.

Get better at things.

Get rid of things.

Keep a toolbox.

Fix things.

Build things.

Study nature.

Be faithful.

Sing.

Tend a garden.

Love water.

Raise animals.

Invite people over.

Open your door.

Age gracefully.

Keep dreaming.

Drink tea.

Love your spouse.

Raise good kids.

Thank teachers.

Call friends.

Talk with neighbours.

Find solitude.

Gather for meals.

Bounce back.

Travel.

Complete tasks.

Be an artist.

Mow your lawn.

Think.

Give small gifts.

Talk to strangers.

Remember names.

Teach what you know.

Build a fire pit.

Speak right from wrong.

Remember your life.

Play with kids.

Accept loss.

Extend conversations.

Visit graveyards.

Clean up.

Avoid gossip.

Vote.

Swim in streams.

Hike trails.

Climb mountains.

Paddle rivers.

Collect seashells.

Be human…

by Fitz | Jul 23, 2015 | Essays, Journal, Teaching

I

The dull staccato throb in light rain on a dark night. Unseen barges make their way up the QianTian River—concrete shores marked by the arch of the bridge, the spans of beam stretched on beam, the impeccable symmetry of the street-lights broken by a stream of impatient headlights—the bursting aorta of commerce and hope that is Hangzhou.

The dull staccato throb in light rain on a dark night. Unseen barges make their way up the QianTian River—concrete shores marked by the arch of the bridge, the spans of beam stretched on beam, the impeccable symmetry of the street-lights broken by a stream of impatient headlights—the bursting aorta of commerce and hope that is Hangzhou.

Or is it the torrent of humanity flowing east and west and north and south around the antiquities of West Lake? Lovers. Couples in every configuration and every intent. Families dragging or being dragged. Packs of friends so hip and cool and daring. So much unlike the China I remember. Soft wool coats: blue or gray. Mao buttons and short-visor caps. I fall just as easily into reverie as anticipation.

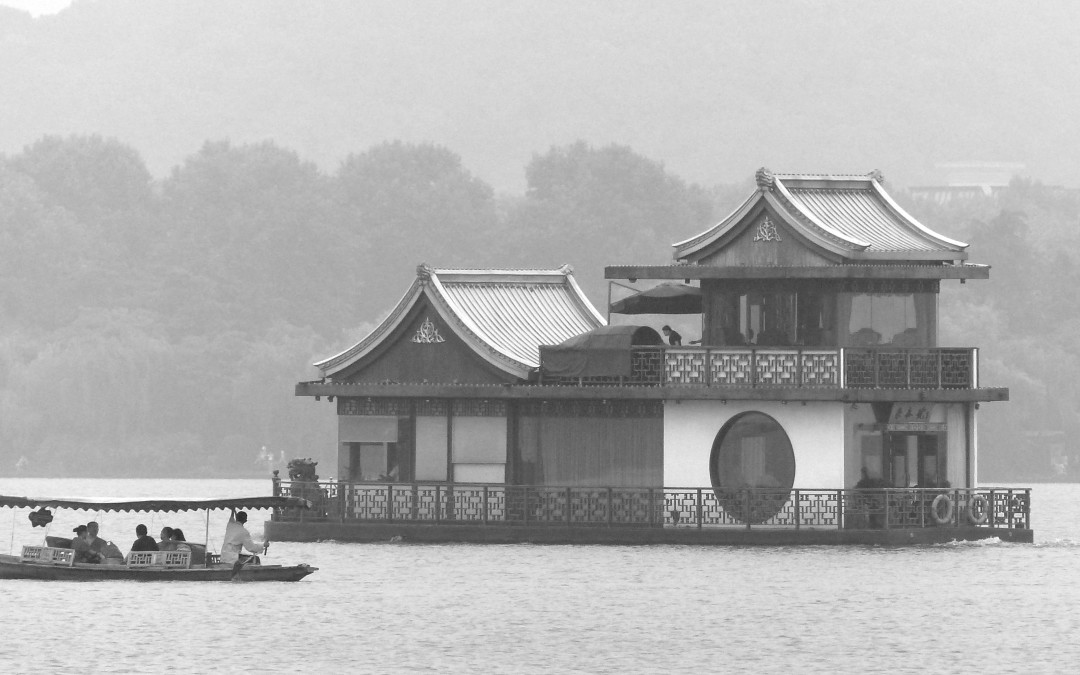

The grey fog and swirl of mist on West Lake outlines the rowing prams and party boats decked in imitation of palaces lost to time. On a far hillside—a bare shape of a gray palace on a gray background. Somewhere within: the lusty cries and plaintive words of crazy Li Po, drunk again and strewing words with a practiced and meticulous abandon—picked up by stooped bodies and weathered visages carried and thrown with feral joy—skipping stones stretched across still waters. Heavy, fluttering weight borne down by inescapable gravity.

Right now I am happy to my bones and as lonely and weak as a man can be. I scroll through pictures of my family and share them with the sky which seems heavy enough to fall—the dirt and smoke and smell of progress. Each picture tugs at my heart. I am not built to be away from home—Tommy scales a rock wall. Emma plays her ukulele. Margaret her guitar. EJ fixes his VW. Charlie juggles a soccer ball. Kaleigh collects seashells and beach glass. Pipo washes enormous pans in the camp kitchen. Denise sits in the backyard—our blessed perfect backyard—holding a chicken. I cling to them as wildly as wild can be. I will dare anyone. Any time. It is not a test I need to prepare for.

The craziness is in the contrast: this city of millions and millions and millions sprouting steel and glass and brick in every configuration of a weedy architect’s dream. I should be happy to be here, but I long for the simplicity of my back porch. Morning coffee with Denise. Kids busy. Friends who call. A slow jog. A bulb that needs to be changed. Only a fool would argue with me.

Jet lag wakes me in the middle of the night. I read Joyce for an hour. Is my head Dadelus or Bloom? It is too easy to confuse work of the head with work. Real work. Whatever it is that I need sleep for? Dave and Rob are still asleep. Long in jealous sleep. Or maybe like me—eyes wide-awake, curious if the sun ever shines in this city? Maybe stuck in fogged memories brushed in Song Dynasty waterstrokes. Rounded bellies surrounded by calligraphy’d words. China is not a country that etched its history on cave walls. Everything flows and dies and recreates itself in an unending cycle of births measured in massive ticks of time. For me and Dave and Rob at least: three days of incessant rain, mist and curiosity; still, I am a silent claw scuttling across the floors of a silent sea.

Yet we laugh as much as men have always laughed at the vagaries of fate in this country which seems to have created the word. We are ecstatic with our luck to be here. We scrounge like beggars for coffee in the morning. We force ourselves into taxis like hobo’s stuffing rucksacks. We teach the new elite of China: sons and daughters of scion and opportunity. Kids only, and no different, as if God only has three or four molds to work with: here is your intense child; here is your dreamy child; here is the child hobbled by a dull mind nurtured in like-minded fanaticism by parents deluded by assumptions of perfection, and here is the kid of the world—the ever-real world—the everywhere world: give me love; give me hope; give me joy; give me space. Save me from yourselves.

We work alongside the young and restless who are torn by conviction and inclination. The young who are prey to vanity, pretence, boldness and unplumbable magnanimity in equal measure. We call them by English names chosen in blithe randomness: this sounds good—I like this name—this is easy to remember—many famous people are named Richard. I want to scream and say that we are not so lost that we can’t remember the tongue-twisters of our youth. It is as easy for us to say to say that one sly snake slid up the stake and the other sly snake slid down as Liu Guo Ping or Ren Qi Wei or Sun Zhu. I like your name. I want your name. Your real name. There is no other way to begin.

Just tell us your name! and maybe the BBC won’t report every day on the gulf between us, on what our misunderstandings are, or on how we need to understand history. We are all ignorant, damn it, in every way, yet we are transcendent in every moment—if given the chance. I don’t want to meet another ex-pat who has been here for three years—or five years—or ten years, for they have nothing to tell me but their story, and as perfect and real as that story may be, I will measure that story against their own ignorance—and then we are surprisingly equal. I need to know that the wisdom of my backyard is as expansive as any unboundaried world. If not, why seek peace? It is unattainable. We do not need travel to suffocate bigotry. We only need to love and accept one thing that is not ours and build from there.

The young teachers from the school where we are working, Arvin, Angie, Addie and Ray, walked us around West Lake tonight—a quartet of twenty-somethings that seems to be the pillars of the new China: modern, ancient, vulnerable, and impertable. Arvin, in almost manic ecstasy, tells story after story of the history, the meaning, and the reality of every turn of the path in spontaneous bursts of every language he knew. Angie and Addie and Ray recreate the meaning, but not the ecstasy, blessed and cursed as they are by the temperance of defined lives.

We feast in some palace by the shore. Table after table full of men doing small shots of incredibly strong liquor—standing like warriors around a magnificent table. Sometimes a table of their wives locked in the chatter of tradition. Sometimes a table like us: a few friends; a few guests, and toasts and laughs in a broken dance of broken language cobbled into some kind of understanding. It almost felt like defiance, a changing of the guard. Sit with your wives, dammit! Yet, I was jealous of their camaraderie of tradition. We men barely change.

We watched a Chinese opera performed on the waters, sitting in the pouring rain surrounded within a sea of flimsy blue poncho’s. I loved my poncho, for it made me as Chinese as the rest of the crowd—my blue tarp like their blue tarp. My Mao jacket and their mao cap. I almost wanted to gasp like the crowd at every cool shift of scenery—of tens of feathers running across the water top—of lovers floating on ancient barges never quite touching prows—of ominous risings and fallings of girded columns of steel rising out of the waters of West Lake. Instead I squinted like an engineer to figure out the mechanism of reality that made people gasp. I regret that this always been my fallback to keep me from the lure of wonderment. I wanted to be lost in amazement, yet I was only gifted by the delight of engagement and deconstruction—the lost twin of faith.

Tonight, like everything, did not end: it was truncated by everything that truncates. It is absurd that I am still awake. Wisdom and experience plead with me to let go of the night, but I can’t, because louder than wisdom of experience is the voice of Li Po. The poet’s guttural cry croaked infinatum. Not unlike the barges—some conveyance I don’t see— a sound, merely, in a gray night, but I feel the dull, throbbing, staccato notes—the predictable heartbeat of a diesel reassurance lurching into the strong, moiling, and unceasing flow of tomorrow.

A tomorrow that is already here.

by Fitz | Mar 1, 2015 | Essays, Journal, Teaching

A literary reflection to my students…

The lowering for whales, the appearance of Fedallah’s crew, the vivid descriptions of the first chase in a sudden and unrelenting gale, the fatalistic joy of resigning oneself to fate, the awesome poetic intensity of Melville’s prose—the intermixing of the mundane with the profound and metaphysical, balancing historical accuracies with inner musings on motives and aspirations all make for a compelling read in chapters 42-51.

There is nothing to get but the sublimity of the experience. These are words that must be read–and perhaps reread many times–to appreciate the accumulating power. To become lost by and in the words of Moby Dick is to be lost in the briny mix of our own lives. I read and my mind wanders and seeps into my own life with its mix of romantic dreams lost in the colder harshness of everyday reality.

I have to let myself be pulled and borne by the power of the sea and the maniacal focus on desire, for somewhere in us is the monomania of Ahab equally balanced by the stoic sense of purpose of Starbuck, the self-abnegating and joyful acceptance of fate in Flask and Stubbs, the sheer wonderment and astonishment of Ishmael to simply be there, the visceral and primal wisdom of Queequeg, and the crazy interplay and intermixing of the crew in their universal worldliness and embrace of a common vision—and Moby Dick, the ubiquitous beast, dream, nightmare, and reality that courses through the pulsing aorta of the narrative.

This reading is not and should not be a chore. It is the adventure itself, and a hard and tasking adventure it is that you are tackling day and day out, no less than the crew itself, for the Pequod is, through better and worse, our classroom and our teacher, and we must all stand watch on the mastheads and scan for distant spouts on a vast horizon even, like the mysterious Fedullah, on nights lit only by the sliver of a moon–framed against the vastness of a cold and unforgiving sea and one man’s usurpation of a collective odyssey.

Keep reading.

by Fitz | Nov 24, 2014 | Essays, Journal, Teaching

“Classic’ – a book which people praise and don’t read.”

~Mark Twain

A note to my 8th grade class:

All of you are supposedly reading a classic book, but what Twain says is true: few of us go thirsty to the well and willingly read the greatest works of literature because…well, just because.

The dutiful among you are simply answering the call of an assignment. Some among you are skimming as much as possible to glean just enough to talk or write intelligently about the book, while the laziest among you are putting off reading as long as possible before I ask you to write something meaningful about what you are reading. And then: thank God for Sparks Notes. You might even get away with it.

But only for a while.

Life has a way of catching up with us in some karma-like way. Nobody I know willingly admits that he or she is a shallow shell of a person masquerading as a carrier of knowledge and wisdom. We need to believe that how we live is not only sustainable, but also healthy and vibrant. But how healthy can we be if our thoughts are only as wild and free as turkeys in a pen? How healthy can we be if the food of our mind is a mush of glutinous starch and sugar? Sooner or later the fat settles in, the muscle fades, and a simple walk down the street feels like an epic journey.

My hope is that whatever you are reading is both exhausting and energizing. I hope you sit down to read and forcefully pry the blinders away from your mind and open yourself to the possibility of a true and profound literary experience. I hope that you are sensing the eternal value of a transient experience. I hope that you are giving a damn and trying to figure out how and why the words you are reading are considered to be classic literature.

The book you are reading is considered a classic not because a coterie of fuddy-duddy English teachers have decided something is deemed to be “required” reading. What you are reading is a classic because the words, plot, and value of the book has been proved time and time again in and through the ravages of time and place. Your book is a mountaineer who has scaled some previously unscalable mountain peak.

You, too, are a mountaineer being led by your efforts to a higher peak than perhaps you have climbed before.

Good books do that. Great books do it over and over and over and over.

At this point you may be tempted to rest in a valley and be satisfied with a more narrow view. My youngest son, Tommy, is working on his 6th grade Explorer Project. His subject is George Mallory, the one who when asked why he climbed the highest mountains, simply said, “Because it’s there.” Mallory died on Mount Everest. He and his partner, Sandy Irvine were last seen in 1924 just 800 feet from the summit. Mallory’s body was found some seventy-five years later. No one knows whether they reached the summit or not.

Keep Mallory’s spirit alive. Read your classic. Keep climbing.

Because it’s there.

by Fitz | Oct 11, 2014 | Essays, Journal, Teaching

It’s not just a couch; it’s a sofa, too

~Fitz

I remember my first year teaching at Fenn—and it was really my first stint as a true worker with responsibilities outside of what I already had in my wheelhouse—and on this day, some twenty something years ago, I could hardly move. Every Columbus Day weekend for as long as I could remember we (gangs of friends and I) would head up to Stinson Lake in New Hampshire where my family had a cottage, and I had my usual agenda of mountain climbing, fishing, or even a last sail on our Sunfish around the amazingly pristine waters on my bucket list for those three days.

But this weekend came to be known as the “weekend of the couch.”

All I seemed to be able to do was sleep. Denise, who was not yet my fiancé, and our pack of friends, seemed to have a ball, but all I could do was wave goodbye or say, “I’ll catch up with you later…” But I never did. I put my head back down and slept, literally, for three days. The mental wear and tear of being a teacher had caught me off guard, for somehow the seemingly mundane lists of things to do never seemed to cease—and I was the shop teacher! I think I would have melted or imploded if I was trying to do what I almost naturally do now. A terse letter then from a parent would have me agonizing over a politely worded response. A student upset with a grade, or a mean friend or teacher, would have me scouring a book of psychology for a solution.

This new job was not as straightforward as singing four hours of songs in a pub, cutting down eight cord of wood, sailing through a storm, setting stones or banging nails in winter cold, finding myself alone and broke in some distant corner of the world—all of which had been a big part of my life until that first fall of teaching—and so I laid myself down to rest as I had never done before, all because being a shop teacher was the toughest job I had ever tried to tackle. That endless stream of enthused boys aged nine to fifteen had done what no other job had ever done: exhausted me simply because they energized some part of me that must have lay dormant for the entirety of my adult life—and at that time I was thirty-five years old for God’s sake!

But now I am fifty-six and have been teaching ever since, more writing and reading than shop—and it is still as hard and exhausting as ever, but in a different way. Even last night—a Friday night—I stayed up until one in the morning reading and commenting on my student’s blog posts and journal entries. I read reams of essays about Walden and Tom Sawyer. I listened to their podcasts and watched their video’s and tried to pen a few words of real praise for every effort they made over the course of the last week, and it reflects a massive amount of effort on their part, but for me, tired as I was, it was not a big effort that drained me; moreover, it was more a celebration of the joy of being a teacher, and I woke up this morning “psyched” to continue what is now a rhythmic cycle more in cadence with the seasons than a Sisyphean effort to push an irregular boulder back up a slaggy, barren mountainside.

It is this way because I work in a place that gives me structure and freedom in equal doses. My bosses never hang behind my shoulder and nitpick my constantly evolving curriculum; my parents don’t scrutinize and dissect my motives, and my co-workers laugh with me, bitch with me, and work just as hard at our collective mission as teachers, as if there is no other way. It is by no means a “dream job,” but my school is a place that allows me to dream as deeply as we hope our students dream. Granted, The Fenn School is a rarified community backed up by an enormous cache of accumulated wealth and uncommon worldly success, but when stripped of these trappings every class is simply a group of kids being asked to do what each of us teachers feel he (it is a boy’s school) need to do, and whatever pressure I feel as a teacher is counterbalanced by an academic freedom that deflates that pressure, and so I wonder if this is an approach that just works for us or if it is a reality that needs to be—or at least could be—emphasized in every school, regardless of wealth, opportunity or standing.

If each classroom becomes a family, then every teacher will respond in ways that transcend the trivial; if every school becomes a community that pulls together through the thick and thin of the vicissitudes of the year and places trust in teachers and students, then maybe (I’d say probably) the first six weeks of school won’t put anyone on the couch.

It’s time now and always to climb that mountain with free and joyous motion.

by Fitz | Oct 3, 2014 | Essays, Journal

Finally, the tall green pines standing sentinel around this cold and black New Hampshire pond are framed in a sky of blue. After a month of steady rains, foggy nights, and misty days, I am reborn into a newly created world—a world that finally answered my prayers: no more trying to find that elusive spot under the camper awning that doesn’t seem to leak; no more running across the wet field dragging Tommy bouncing and laughing like a half-inflated beach toy towards a smokey campfire: and (almost regrettably) no more endless scrabble, card games, monopoly, and shallow books. This fresh blue morning barks out the possibilities of the day: Here is my rope-swing. Here are my trails. There lie my waters….

The window is small and the day is large. I shouldn’t even be here teasing words from an empty page when I should be embracing the possibilities of today. As Thoreau said: My life is the poem I should have writ/ But, I could not both live and utter it. The ignorant and lazy part of us might want to rally around Thoreau’s sentiment and say, “Amen to that,” but we would miss the irony and wistfulness of our collective predicament: like kids balancing on a plank set on a log, we scramble back and forth to find that sweet spot on the plank, that place of perfect balance between the forces of yin and yang—but, if we find that spot, we allow ourselves only a few moments of self-indulgent awe before searching for a more elusive and demanding challenge.

To live fully, we must be bored quickly by the easy and mundane. We have to set a larger plank across a bigger log. There is no legal limit to how many balls a juggler can have in the air. We are only captive to gravity and the sun ticking its way towards the horizon.

I need this blue sky to let me see the horizon and the infinite juxtapositions between the earth and sky. I need to be reminded that my page will always be empty if I don’t embrace the day that comes before it. I need to rush headlong into the blinding light. I need to fall and get up time and time again with a contagious and courageous rhythm, and I need to remember to spend my day and not simply save it, as if I could redeem it tomorrow.

My life and my words are my final redemption, woven and rushed imperfectly into the rags I wear.

~Windsor Mountain, 2011