Barbara Allen

(Child Ballad #84)

All in the merry month of May,

When green buds they were swellin’

Young Willie Grove on his death-bed lay,

For love of Barb’ra Allen.

He sent his servant to her door

To the place where he was dwellin’

Make heed, make heed to my master’s call,

If your name be Barb’ra Allen.

Slowly, slowly she up,

And slowly drew she nigh him,

And all she said when there she came:

“Young man, I think you’re dying!”

He turned his pale face to the wall

And death was drawing nigh him.

Good bye, Good bye my dear friends all,

Be kind to Barb’ra Allen

When he was dead and laid in grave,

She heard the death bell knelling.

And every note did seem to say

Oh, cruel Barb’ra Allen.

“Oh mother, mother, make my bed

Make it soft and narrow

Sweet William died, for love of me,

And I shall of sorrow.”

They buried her in the old churchyard

Sweet William’s grave was nigh hers,

And from his grave grew a red, red rose;

From hers a cruel briar.

They grew and grew up the old church spire

Until they could grow no higher

And there they twined, in a true love knot,

The red, red rose and the briar.

If you have any more information to share about this song or helpful links, please post as a comment.

Thanks for stopping by the site!

~John Fitz

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I share their research on my site with humility, thanks, and gratitude. Please cite their work accordingly with your own research. If you have any research or sites you would like to share on this site, please post in the comment box. Thanks!

Contents

| "Barbara Allen" | |

|---|---|

Song lyrics published 1840 in the Forget Me Not Songster | |

| Song | |

| Published | 17th century (earliest known) |

| Genre | Broadside ballad, folksong |

| Songwriter(s) | Unknown |

"Barbara Allen" (Child 84, Roud 54) is a traditional folk song that is popular throughout the English-speaking world and beyond. It tells of how the eponymous character denies a dying man's love, then dies of grief soon after his untimely death.

The song began as a ballad in the seventeenth century or earlier, before quickly spreading (both orally and in print) throughout Britain and Ireland and later North America.[1][2][3] Ethnomusicologists Steve Roud and Julia Bishop described it as "far and away the most widely collected song in the English language—equally popular in England, Scotland and Ireland, and with hundreds of versions collected over the years in North America."[4]

As with most folk songs, "Barbara Allen" has been published and performed under many different titles, including "The Ballet of Barbara Allen", "Barbara Allen's Cruelty", "Barbarous Ellen",[5] "Edelin", "Hard Hearted Barbary Ellen", "Sad Ballet Of Little Johnnie Green", "Sir John Graham", "Bonny Barbara Allan", "Barbry Allen" among others.[6]

Synopsis

The ballad generally follows a standard plot, although narrative details vary between versions.

- A servant asks Barbara to attend on his sick master.

- She visits the bedside of the heartbroken young man, who then pleads for her love.

- She refuses, claiming he had slighted her while drinking with friends.

- He dies soon after and Barbara hears his funeral bells tolling; stricken with grief, she dies as well.

- They are buried in the same church; a rose grows from his grave, a briar from hers, and the plants form a true lovers' knot.[7][5]

History

A diary entry by Samuel Pepys on 2 January 1666 contains the earliest extant reference to the song.[3] In it, he recalls the fun and games at a New Years party:

...but above all, my dear Mrs Knipp, with whom I sang; and in perfect pleasure I was to hear her sing, and especially her little Scotch song of Barbary Allen.[8]

From this, Steve Roud and Julia Bishop have inferred the song was popular at that time, suggesting that it may have been written for stage performance, as Elizabeth Knepp was a professional actress, singer, and dancer.[4] However, the folklorists Phillips Barry and Fannie Hardy Eckstorm were of the opinion that the song "was not a stage song at all but a libel on Barbara Villiers and her relations with Charles II".[9] Charles Seeger points out that Pepys' delight at hearing a libelous song about the King's mistress was perfectly in character.[9]

In 1792, the renowned Austrian composer Joseph Haydn arranged "Barbara Allen" as one of over 400 folk song arrangements commissioned by George Thomson and the publishers William Napier and William Whyte.[10][11] He probably took the melody from James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion, c.1750.[12]

Early printed versions

One 1690 broadside of the song was published in London under the title "Barbara Allen's cruelty: or, the young-man's tragedy" (see lyrics below). With Barbara Allen's [l]amentation for her unkindness to her lover, and her self".[13]

Additional printings were common in Britain throughout the eighteenth century. Scottish poet Allan Ramsay published "Bonny Barbara Allen" in his Tea-Table Miscellany published in 1740.[14] Soon after, Thomas Percy published two similar renditions in his 1765 collection Reliques of Ancient English Poetry under the titles "Barbara Allen's Cruelty" and "Sir John Grehme and Barbara Allen".[15] Ethnomusicologist Francis James Child compiled these renditions together in the nineteenth century with several others found in the Roxburghe Ballads to create his A and B standard versions,[7] used by later scholars as a reference.

The ballad was first printed in the United States in 1836.[citation needed] Many variations of the song continued to be printed on broadsides in the United States through the 19th and 20th centuries. Throughout New England, for example, it was passed orally and spread by inclusion in songbooks and newspaper columns, along with other popular ballads such as "The Farmer's Curst Wife" and "The Golden Vanity".[16]

The popularity of printed versions meant that lyrics from broadsides greatly influenced traditional singers; various collected versions can be traced back to different broadsides.[9]

Traditional recordings

According to the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, approximately 500 traditional recordings of the song have been made.[17] The earliest recording of the song is probably a 1907 wax cylinder recording by composer and musicologist Percy Grainger of the Lincolnshire folk singer Joseph Taylor,[18] which was digitised by the British Library and can now be heard online via the British Library Sound Archive.[19] Other authentic recordings include those of African American Hule "Queen" Hines of Florida (1939),[20] Welshman Phil Tanner (1949),[21] Irishwoman Elizabeth Cronin (early 1950s),[22] Norfolk folk-singer Sam Larner (1958),[23] and Appalachian folk singer Jean Ritchie (1961).[24][25] Charles Seeger edited a collection released by the Library of Congress entitled Versions and Variants of Barbara Allen from the Archive of Folk Song as part of its series Folk Music of the United States. The record compiled 30 versions of the ballad, recorded from 1933 to 1954 in the United States.[9]

Lyrics

"Barbara Allen's cruelty: or, the young-man's tragedy" (c.1690), the earliest "Barbara Allen" text:

In Scarlet Town, where I was bound,

There was a fair maid dwelling,

Whom I had chosen to be my own,

And her name it was Barbara Allen.

All in the merry month of May,

When green leaves they was springing,

This young man on his death-bed lay,

For the love of Barbara Allen.

He sent his man unto her then,

To the town where she was dwelling:

'You must come to my master dear,

If your name be Barbara Allen.

'For death is printed in his face,

And sorrow's in him dwelling,

And you must come to my master dear,

If your name be Barbara Allen.'

'If death be printed in his face,

And sorrow's in him dwelling,

Then little better shall he be

For bonny Barbara Allen.'

So slowly, slowly she got up,

And so slowly she came to him,

And all she said when she came there,

Young man, I think you are a dying.

He turnd his face unto her then:

'If you be Barbara Allen,

My dear,' said he, 'Come pitty me,

As on my death-bed I am lying.'

'If on your death-bed you be lying,

What is that to Barbara Allen?

I cannot keep you from [your] death;

So farewell,' said Barbara Allen.

He turnd his face unto the wall,

And death came creeping to him:

'Then adieu, adieu, and adieu to all,

And adieu to Barbara Allen!'

And as she was walking on a day,

She heard the bell a ringing,

And it did seem to ring to her

'Unworthy Barbara Allen.'

She turnd herself round about,

And she spy'd the corps a coming:

'Lay down, lay down the corps of clay,

That I may look upon him.'

And all the while she looked on,

So loudly she lay laughing,

While all her friends cry'd [out] amain,

'Unworthy Barbara Allen!'

When he was dead, and laid in grave,

Then death came creeping to she:

'O mother, mother, make my bed,

For his death hath quite undone me.

'A hard-hearted creature that I was,

To slight one that lovd me so dearly;

I wish I had been more kinder to him,

The time of his life when he was near me.'

So this maid she then did dye,

And desired to be buried by him,

And repented her self before she dy'd,

That ever she did deny him.

Variations

The lyrics are nowhere near as varied across the oral tradition as would be expected. This is because the continuous popularity of the song in print meant that variations were "corrected".[9] Nonetheless, American folklorist Harry Smith was known to, as a party trick, ask people to sing a verse of the song, after which he would tell what county they were born in.[26]

Setting

The setting is sometimes "Scarlet Town". This may be a punning reference to Reading, as a slip-song version c. 1790 among the Madden songs at Cambridge University Library has 'In Reading town, where I was bound.' London town and Dublin town are used in other versions.[27][28]

The ballad often opens by establishing a festive time frame, such as May, Martinmas, or Lammas. The versions which begin by mentioning "Martinmas Time" and others which begin with "Early early in the spring" are thought to be the oldest and least corrupted by more recent printed versions.[citation needed]

The Martinmas variants, most common in Scotland, are probably older than the Scarlet Town variants, which presumably originated in the south of England. Around half of all American versions take place in the month of May; these versions are the most diverse, as they appear to have existed within the oral tradition rather than on broadsides.[9]

After the setting is established, a dialogue between the two characters generally follows.[29]

Protagonists

The dying man is called Sir John Graeme in the earliest known printings. American versions of the ballad often call him some variation of William, James, or Jimmy; his last name may be specified as Grove, Green, Grame, or another.[30] In most English versions, the narrator is often the unnamed male protagonist.[citation needed]

The woman is called "Barbry" rather than "Barbara" in almost all American versions and some English versions, and "Bawbee" in many Scottish versions. Her name is sometimes "Ellen" instead of "Allen".[citation needed]

Symbolism and parallels

The song often concludes with poetic motif of a rose growing from his grave and a brier from hers forming a "true lovers' knot", which symbolises their fidelity in love even after death.[31] This motif is paralleled in several ballads including "Lord Thomas and Fair Annet", "Lord Lovel", and "Fair Margaret and Sweet William".[30][9] However, the ballad lacks many of the common phrases found in ballads of similar ages (e.g. mounting a "milk white steed and a dapple" grey), possibly because the strong story and imagery means these cliches are not required.[9]

Melody

A vast array of tunes were traditionally used for "Barbara Allen". Many American versions are pentatonic and without a clear tonic note,[9] such as the Ritchie family version. English versions are more rooted in the major mode. The minor-mode Scottish tune seems to be the oldest, as it is the version found in James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion which was written in the mid-1700s.[32] That tune survived in the oral tradition in Scotland until the twentieth century; a version sung by a Mrs. Ann Lyell (1869–1945) collected by James Madison Carpenter from in the 1930s can be heard on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library website,[33] and Ewan MacColl recorded a version learned from his mother Betsy Miller.[34] Whilst printed versions of the lyrics influenced the versions performed by traditional singers, the tunes were rarely printed so they are thought to have been passed on from person to person through the centuries and evolved more organically.[9]

Popular arrangements and commercial recordings

Roger Quilter wrote an arrangement in 1921, dedicated to the noted Irish baritone Frederick Ranalow, who had become famous for his performance as Macheath in The Beggar's Opera at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. Quilter set each verse differently, using countermelodies as undercurrents. An octave B with a bare fifth tolls like a bell in the fourth verse. A short piano interlude before the fifth verse was commented on favourably by Percy Grainger.[35] Quilter later incorporated the setting in his Arnold Book of Old Songs, rededicated to his late nephew Arnold Guy Vivian, and published in 1950.[36]

Baritone vocalist Royal Dadmun released a version in 1922 on Victor Records. The song is credited to the arrangers, Eaton Faning and John Liptrot Hatton.[37] British composer Florence Margaret Spencer Palmer published Variations on Barbara Allen for piano in 1923.[38]

Versions of the song were recorded in the 1950s and '60s by folk revivalists, including Pete Seeger. Eddy Arnold recorded and released a version on his 1955 album "Wanderin'". The Everly Brothers recorded and released a version on their 1958 folk album, "Songs Our Daddy Taught Us". Joan Baez released a version in 1961, the same year as Jean Ritchie's recording.[39] Bob Dylan said that folk songs were highly influential on him, writing in a poem that "[w]ithout "Barbara Allen there'd be no 'Girl from the North Country'; Dylan performed a live eight-minute rendition in 1962 which was subsequently released on Live at The Gaslight 1962.[40]

The demo of the ballad recorded by Simon and Garfunkel appears on their anthology album The Columbia Studio Recordings (1964-1970) and a bonus track on the 2001 edition of their album Sounds of Silence as "Barbriallen",[41] and by Art Garfunkel alone in 1973 on his album Angel Clare.

June Tabor, the English folk singer includes the song as "Barbry Allen" on her 2001 album Rosa Mundi.[42] Angelo Branduardi recorded this song as Barbrie Allen resp. Barbriallen on his two music albums Così è se mi pare – EP[43] " and Il Rovo e la rosa[44] in Italian. On his French EN FRANÇAIS – BEST OF compilation in 2015 he sang this song in French-adaption written by Carla Bruni.[45][46]

English singer-songwriter Frank Turner often sings the song a cappella during live performances. One rendition is included on the compilation album The Second Three Years.[47]

UK folk duo Nancy Kerr & James Fagan included the song on their 2005 album Strands of Gold,[48] and also on their 2019 live album An Evening With Nancy Kerr & James Fagan.[49][50]

The Renaissance folk-rock band Blackmore's Night include the song on their 2010 album Autumn Sky.

Popular culture adaptations and references

The song has been adapted and retold in numerous non-musical contexts. In the early twentieth century, the American writer Robert E. Howard wove verses of the song into a civil war ghost story that was posthumously published under the title ""For the Love of Barbara Allen"."[51] Howard Richardson and William Berney's 1942 stage play Dark of the Moon is based on the ballad, as a reference to the influence of English, Irish and Scottish folktales and songs in Appalachia. It was also retold as a radio drama on the program Suspense, which aired 20 October 1952, and was entitled "The Death of Barbara Allen" with Anne Baxter in the titular role. A British radio play titled Barbara Allen featured Honeysuckle Weeks and Keith Barron; it was written by David Pownall[52] and premiered on BBC Radio 7 on 16 February 2009.[53] In The Hunger Games prequel novel The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, characters from the Covey are given first names based on traditional ballads. The character Barb Azure Baird's first name is based on Barbara Allen.

The song has also been sampled, quoted, and featured as a dramatic device in numerous films:

- Tom Brown's School Days (1940)

- Scrooge (1951; released in the U.S. as A Christmas Carol)

- Robin Hood Daffy (1958; Warner Brothers cartoon)

- The Buccaneer (1958), sung by Claire Bloom.

- Parker Adderson, Philosopher (1974; short film[54])

- Jane Campion's Oscar-winning The Piano (1993)

- Best in Show (2000)

- Songcatcher (2000)

- A Love Song for Bobby Long (2004)[55]

References

- ^ Raph, Theodore (1 October 1986). American Song Treasury: 100 Favorites. Dover. p. 20.

This folk song originated in Scotland and dates back at least to the beginning of the seventeenth century

- ^ Arthur Gribben, ed., The Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America, University of Massachusetts Press (1 March 1999), pg. 112.

- ^ a b "Late Junction: Never heard of Barbara Allen? The world's most collected ballad has been around for 450 years". BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b Roud, Steve & Julia Bishop (2012). The New Penguin Book of Folk Songs. Penguin. pp. 406–7. ISBN 978-0-141-19461-5.

- ^ a b Coffin, Tristram P. (1950). The British Traditional Ballad in North America. Philadelphia, PA: The American Folklore Society. pp. 87–90.

- ^ Keefer, Jane (2011). "Barbara/Barbry Allen". Ibiblio. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ a b Child, Francis James (1965). The English and Scottish Popular Ballads Vol. 2. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 276–9.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel. Diary of Samuel Pepys — Volume 41: January/February 1665–66. Project Gutenberg.

Pepys – Diary – Vol 41

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Versions and Variants of the Tunes of "Barbara Allen"" (PDF). Library of Congress.

- ^ "Barbara Allen, Hob.XXXIa:11 (Haydn, Joseph) – IMSLP: Free Sheet Music PDF Download". imslp.org. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Folksong Arrangements by Haydn / Folksong Arrangements by Haydn and Beethoven / Programmes / Home – Trio van Beethoven". www.triovanbeethoven.at. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "The Caledonian Pocket Companion (Oswald, James) – IMSLP: Free Sheet Music PDF Download". imslp.org. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "English Short-title Catalogue, "Barbara Allen's cruelty: or, the young-man's tragedy."". British Library. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Ramsay, Allan (1740). "The tea-table miscellany: or, a collection of choice songs, Scots and English. In four volumes. The tenth edition". Internet Archive. pp. 343–4. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Percy, Thomas (1 December 2018). "Reliques of Ancient English Poetry: Consisting of Old Heroic Ballads, Songs, and Other Pieces of Our Earlier Poets; Together with Some Few of Later Date". F.C. and J. Rivington – via Google Books.

- ^ Post, Jennifer (2004). Music in Rural New England. Lebanon, NH: University of New Hampshire Press. pp. 27–9. ISBN 1-58465-415-5.

- ^ "Search: "RN54 sound"". Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

- ^ "Percy Grainger's collection of ethnographic wax cylinders". British Library. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Barbara Ellen – Percy Grainger ethnographic wax cylinders – World and traditional music | British Library – Sounds". sounds.bl.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Barbara Allen (Roud Folksong Index S228281)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Barbara Allen (Roud Folksong Index S136912)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Barbara Allen (Roud Folksong Index S339062)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Barbara Allen (Roud Folksong Index S168428)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Barbry Ellen (Roud Folksong Index S415160)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Barbara Allen / Barbary Allen / Barbary Ellen (Roud 54; Child 84; G/D 6:1193; Henry H236)". mainlynorfolk.info. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ A Booklet of Essays, Appreciations, and Annotations Pertaining to the Anthology of American Folk Music Edited by Harry Smith. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. 1997. pp. 30–31, sidebar featuring story told by Lucy Sante.

- ^ "The Ballad of Barbara Allen by Anonymous". PoetryFoundation.org. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Bonny Barbara Allan, Traditional Ballads, English Poetry I: from Chaucer to Gray". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Sauer, Michelle (2008). The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry Before 1600. Infobase Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 9781438108346. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ a b Coffin, Tristram P. (1950). The British Traditional Ballad in North America. Philadelphia: The American Folklore Society. pp. 76–9, 87–90.

- ^ Würzbach, Natascha; Simone M. Salz (1995). Motif Index of the Child Corpus: The English and Scottish Popular Ballad. Gayna Walls (trans.). Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 25, 57. ISBN 3-11-014290-2.

- ^ "(69) Page 27 – Barbara Allan – Inglis Collection of printed music > Printed music > Composite music volume > Caledonian pocket companion – Special collections of printed music – National Library of Scotland". digital.nls.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Bonnie Barbara Allan (VWML Song Index SN23862)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Bawbee Allan (Child 84) (1966) – Ewan MacColl". YouTube. 6 May 2020.

- ^ Langfield, Valerie (1 December 2018). Roger Quilter: His Life and Music. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851158716 – via Google Books.

- ^ Web(UK), Music on the. "Roger QUILTER Folk-songs and Part-songs NAXOS 8.557495 [AO]: Classical CD Reviews- June 2005 MusicWeb-International". www.musicweb-international.com.

- ^ "Browse All Recordings | Barbara Allen, Take 4 (1922-04-05) | National Jukebox". Loc.gov. 5 April 1922. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International Encyclopedia of Women Composers. Books & Music (USA). ISBN 978-0-9617485-1-7.

- ^ Wilentz, Sean; Marcus, Greil, eds. (2005). The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 13–4.

- ^ Wilentz & Marcus 2005, p. 14-15.

- ^ "The Columbia Studio Recordings (1964–1970) – The Official Simon & Garfunkel Site". Simonandgarfunkel.com. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "Barbara Allen / Barbary Allen / Barbary Ellen". Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music.

- ^ "Angelo Branduardi – Cosi È Se Mi Pare". Angelobranduardi.it. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Michele Laurent. "IL ROVO E LA ROSA Angelo Branduardi". Angelobranduardi.it. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "En français – Best Of – Angelo Branduardi". Wmgartists.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "Angelo Branduardi – Best Of En Français (CD, Compilation)". Discogs. 2015.

- ^ "The Second Three Years | Frank Turner". frank-turner.com. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "Nancy Kerr & James Fagan – Strands of Gold". www.discogs.com. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "An Evening With Nancy Kerr & James Fagan". www.kerrfagan.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "Nancy Kerr & James Fagan:An Evening With – Folk Radio". www.folkradio.co.uk. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Howard, Robert E. (2007). The Best of Robert E. Howard. Volume 1: Crimson Shadows. Del Rey Books. pp. 249–55. ISBN 978-0-345-49018-6.

- ^ "Barabara Allen by David Pownall". Radio Drama Reviews.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "David Pownall – Barbara Allen broadcast history". BBC Online. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ An episode of the PBS TV series The American Short Story. A full version of the song is performed in this adaptation of an Ambrose Bierce story of the American Civil War.

- ^ "Travolta Sings For 'Bobby Long'". Billboard. 29 December 2004. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

External links

- Late 17th-century English broadside printing of "Barbara Allen's Cruelty", via the British Library's Roxburghe collection

- Scan of "Bonny Barbara Allen" in 1904 edition of Child's English and Scottish Popular Ballads at Google Books

- Recording of "Barbara Allen" as performed by Frank Luther in 1928 at Project Gutenberg

- Scan of "Barbara Allan" broadside printed in 1855

- Contemporary sheet music for one version of the song

- Online transcripts of Barbara Allen

- Recordings for the ballad are also available at the English Broadside Ballad Archive at University of California, Santa Barbara

- A list of performances and recordings of the song can be found at Mainly Norfolk.

Barbara Allen / Barbary Allen / Barbary Ellen

[ Roud 54 ; Child 84 ; G/D 6:1193 ; Ballad Index C084 ; Bodleian Roud 54 ; Wiltshire Roud 54 ; trad.]Phil Tanner sang Barbara Allen on a BBC recording made on April 22, 1949 at Penmaen, Wales. It was included on the anthology The Child Ballads 1 (The Folk Songs of Britain Volume 4; Caedmon 1961; Topic 1968), in 1968 on his eponymous EFDSS album, Phil Tanner, and in 2003 on his Veteran anthology CD The Gower Nightingale.

Elizabeth Cronin was recorded singing Barbara Allen in Ballyvourney, County Cork, in the early 1950s. This recording was included in 2012 on the Topic anthology Good People, Take Warning (The Voice of the People Series Volume 23). Steve Roud commented:

“This little song of a spineless lover who gives up the ghost without a struggle and of his spirited beloved who repents too late, has paradoxically shown a stronger will-to-live than perhaps any other ballad in the canon.” This is how Bertrand Bronson introduces Barbara Allen, which is easily the most widely known of the Child ballads. Hundreds of versions have been collected across Britain and North America since systematic song-fieldwork began in the late 19th century, and dozens of broadside printings are known. Although Child himself only devoted three meagre pages to the ballad, Bronson musters an impressive 198 versions with tunes. It is not easy to account for this popularity, although the fact that it was incorporated into ‘national’ and school songbooks and poetry anthologies must have helped to keep it in the public eye.

Bess Cronin’s version of the story is stripped down to its bare essentials, and one extremely important element is omitted: Barbara’s dying soon afterwards. In some versions, Barbara’s ‘cruel’ behaviour is simply the result of feminine pique. The young men were in the tavern drinking healths to the girls, but they left her our, and therefore slighted her. But in very many versions, even this slender motive is absent, and Barbara’s spite is unexplained. Ballad enthusiasts abhor a vacuum, so various ingenious, but groundless, claims have been made which brand Barbara as, for example, a witch who has cast a spell on her lover, or even that she was a prostitute, on the strength of the regular opening line “In Scarlet Town where I was born”. The fact that the latter probably refers to the well-documented nickname for Reading, which is where many versions are set, counts for nothing in this attempt to make Barbara a ‘scarlet woman’.

The earliest known texts date from the mid-18th century, but we know that the song was much older than that, as Samuel Pepys, who was an enthusiastic amateur musician, recorded hearing it as a social gathering on the 2nd January 1666. His diary reads: “but above all my dear Mrs. Knipp, with whom I sang; and in perfect pleasure I was to hear her sing, and especially her little Scotch song of Barbary Allen.” Elizabeth Knepp (Knipp) was an actress, singer, and dancer in the King’s Company. She features regularly in Pepys’ diary, and he nicknamed her ‘Bab Allen’.

Jessie Murray sang Barbara Allen at the 1951 Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh; a CD with recordings from this event was published by Rounder Records in 2005.

The Shropshire farm worker Fred Jordan sang Barbara Allen on October 30, 1952 to Peter Kennedy. This recording was included in 2003 on his Veteran anthology A Shropshire Lad. A recording made by Tony Foxworthy in 1974 was published in the same year on his Topic album When the Frost Is on the Pumpkin.

Charlie Wills of Bridport, Dorset, sang Barbara Allen in 1952 to Peter Kennedy and in 1971 to Bill Leader. The former recording was included on the anthologyThe Child Ballads 1 (The Folk Songs of Britain Volume 4; Caedmon 1961; Topic 1968), and the latter in 1972 on his eponymous Leader album, Charlie Wills.

Charlie Scamp sang Barbary Allen to Peter Kennedy and Maud Karpeles at Chartham Hatch, near Canterbury, Kent, on January 15, 1954. This recording was included in 2012 on the Topic anthology I’m a Romany Rai (The Voice of the People Volume 22).

Ewan MacColl sang Bawbee Allen on his and A.L. Lloyd’s 1956 Riverside anthology The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (The Child Ballads) Volume II. He also sang Barbara Allen in 1966 on his Topic album The Manchester Angel. He commented in the latter album’s notes:

This is, by far, the most popular of the traditional ballads. It has been printed in chapbooks and broadsides and, on more than one occasion, has served as a stage song. The widespread oral circulation of the ballad has resulted in many minor variations of plot and, as Professor Bronson has observed, its tough-minded heroine has, with the passing of time, been transformed into a properly penitent young lady. The bequests mentioned in stanzas 4 and 5 were considered by Child to be interpolations not properly belonging to the ballad. The version given here was learned from Caroline Hughes in 1964.

Sam Larner of Winterton, Norfolk, sang Barbara Allen on March 7, 1958 to Philip Donnellann. This BBC recording was published in 1974 on his Topic album A Garland for Sam. Another recording made by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger in 1958-60 was included in 2014 on Larner’s Musical Traditions anthologyCruising Round Yarmouth.

Shirley Collins sang Barbara Allen on two of her albums: in 1959 on Sweet England and in 1967 on The Power of the True Love Knot. She commented in the latter album’s notes:

Barbara Allen is the “dark lady” of the ballads. She has been known to skip out of Jimmy’s reach as he stretches a pale arm for her from his death bed; laugh out loud as she sees Jimmy’s ghost in the lane on her way home. But after her devilish behaviour she always dies of remorse and finishes up in the churchyard with Jimmy. Of all the many versions I have heard, this one, with its sad two-part tune, haunts me most and best seems to evoke Barbara Allen herself.

Jim Wilson of West Hoathly, Sussex, sang Barbara Allen to Mervyn Plunkett in June 1959. This recording was included in 1961 on the Collector anthologyFour Sussex Singers. Another recording made by Brian Matthews at The Plough, Three Bridges, on February 10, 1960 was included in 2001 on the Musical Traditions anthology of songs from country pubs, Just Another Saturday Night. The latter’s booklet commented:

It’s always nice to hear a good version of Barbara Allen—and this is a really good one, with a fairly full text, and the unusual ‘little hearts’ line. The tune skips about from 4/4 to 6/8 in a delightful way and Jim’s occasional short lines are just glorious. A superb performance.

Robin Hall sang Bawbie Allen in 1960 on his Collector album of ballads from the Gavin Greig Collection, Last Leaves of Traditional Ballads.

Lucy Stewart of Fetterangus sang Barbara Allen in 1961 to Kenneth K. Goldstein. This recording was published in the same year on her Folkways albumTraditional Singer from Aberdeenshire, Scotland, Vol. 1—Child Ballads. Goldstein commented:

In his diary entry for January 2, 1666, Samuel Pepys wrote: “In perfect pleasure I was to her her (Mrs. Knipp, an actress) sing, and especially her little Scotch song of Barbary Allen.” Many others have shared his “perfect pleasure” since Pepys’ days, for Barbara Allen is certainly the best known and most widely sung of the Child ballads.

The consistency of the basic outline of the story and the amazing number of texts which have been reported on both sides of the ocean is no doubt due, in large part, to the numerous songster, chapbook and broadside printings of the ballad in the 19th century. A widespread oral circulation has, however, left its mark, for no ballad shows, in its different variants, so many minor variations.

The bedside gifts of the dying youth occurs frequently in Scottish texts of the ballad; Child however would not recognise this as legitimately belonging to the ballad, with the result that he omitted from his canon a version containing such bequests.

In most Scottish versions, the dying lover’s name is John Graeme. Lucy’s text omitting this point, together with the placing of the tale in London, suggests a possible combination in tradition of Scottish and English variants.

Caroline Hughes sang Barbry Allen in a recording made by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger in 1964 that was included in 2014 on her Musical Traditions anthology Sheep-Crook and Black Dog, and John Hughes sang it to Peter Kennedy in Caroline Hughes’ caravan near Blandford, Dorset, on April 19, 1968. This recording was included in 2012 on the Topic anthology I’m a Romany Rai (The Voice of the People Volume 22). Rod Stradling commented in the former anthology’s booklet:

This is the most widely-known ballad I’ve yet encountered in Steve Roud’s Song Index, with an astonishing 1191 instances (including 311 sound recordings) listed there. Needless to say, it’s found everywhere English is spoken—though Australia boasts only one version in the Index—and, very unusually, there’s even one from Wales … although it comes from Phil Tanner in that ‘little England’, the Gower Peninsula. The USA has 600 entries! It doesn’t appear to be quite so well-known in Ireland, with only 35 Index instances, or Scotland with 61.

The story comes in two general types: in one, Barbara upbraids Johnny for slighting her, and leaves him to die; in the other, she laughs at his corpse and is condemned as ‘cruel-hearted’ by their friends standing by. In both cases ‘It was he that died for love, and she that died of sorrow’. The ‘gold watch’ and ‘bowl of tears/blood’ verses which make up much of Mrs Hughes’ version can be found in either type. Her ‘I picked her out for to be my bride’ line in the first verse is very unusual; I’ve only heard it in the Jim Wilson (MTCD309-0) version, noted below. The ballad frequently ends with the rose and briar tied in a true-lovers’ knot motif, seemingly floated in from the Lord Lovell ballads.

Joe Heaney sang Barbary Ellen to Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger in 1964 too. This recording was included in 2000 on his Topic anthology The Road from Connemara.

Scan Tester sang Barbara Allen at The Fox in Islington, London, on January 21, 1965. This recording made by Reg Hall was published in 1990 on Tester’s Topic album I Never Played to Many Posh Dances.

Hedy West sang Barbara Allen on her album Old Times & Hard Times (Topic 1965; Folk-Legacy 1967). This recording was also included in 2011 on her Fellside anthology Ballads & Songs from the Appalachians. The original album’s liner notes commented:

This favourite ballad, with its story that seems singularly passive when one considers what blood-bolstered narratives most folk ballads are, is enormously widespread in the upland South of the United States, and in one state alone—Virginia—ninety-two different versions were collected. It probably owes its impressive survival to the fact that it was so often reprinted during the nineteenth century on broadsides and in cheap songbooks. Hedy West says: “I have rarely collected folk songs from any singer who didn’t know some variant of this ballad. The basic text is from Uncle Gus Mulkey. I’ve made textual and melodic additions from other sources.”

Danny Brazil sang Barbary Allen at his trailer at Over Bridge caravan site to Peter Shepheard on January 6, 1966, and Debbie and Pennie Davies sang it to Mike Yates near the Northfields housing estate, Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire. Both recordings were included in 2007 on the Brazil family’s Musical Tradition anthology Down By the Old Riverside. The latter was previously included in 1979 on the Topic anthology of songs, stories and tunes from English gypsies,Travellers.

Sarah Makem sang Barbara Allen to Bill Leader in her home in Keady, Co. Armagh in 1967. This recording was published a year later on the Topic albumUlster Ballad Singer and in 1998 on the Topic anthology It Fell on a Day, a Bonny Summer Day (The Voice of the People Series Volumes 17). Another, much earlier, recording made by Diane Hamilton in 1955 was published in 2012 on Sarah Makem’s Topic CD The Heart is True (The Voice of the People Series Volumes 24). Sean O’Boyle commented in her first album’s sleeve notes:

Everyone knows the tragic story of young Jemmy Grove and Hard-Hearted Barbara Allen. One look through the list of texts and tunes given in Cecil Sharp’s English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians will show its widespread popularity. It is recorded in Shropshire Folklore(p 543), Folk-Songs of the Upper Thames (p 204), Folksongs from Somerset (No. 22) and in Gavin Greig’s Last Leaves (No. 32), in Mackenzie’s Ballads and Sea Songs of Nova Scotia (No. 9), in British Ballads from Maine, in Traditional Ballads of Virginia, and in Folksongs of the Kentucky Mountains, and elsewhere. In all, more than 200 variants of the ballad are known from printed sources and recordings. This version from Keady, Co. Armagh is as good as any I have heard, and it differs from all of them in one remarkable respect. Most versions place the tragedy

“in the merry month of may

when the green buds they were swelling”,but Sarah’s song has a more sombre and appropriate timing:

Michael’s Mass (Michaelmas) day being in the year

When the green leaves they were falling,

When young Jemmy Grove from the North Countrie

Fell in love with Barbara Allen.

George Belton of Madehurst, Arundel, Sussex, sang Barbara Allen on January 29, 1967 to Sean Davies and Tony Wales. This recording was published in the same year on his EFDSS album All Jolly Fellows ….

Cecilia Costello sang Barbara Allen in 1967 to Charles Parker and Pam Bishop. This recording was included in 2014 on her Musical Traditions anthology Old Fashioned Songs.

Packie Manus Byrne sang Barbara Ellen in 1969 on his eponymous EFDSS album Packie Byrne.

Bob Hart of Snape, Suffolk, sang Barbara Allen on July 8, 1969 to Rod and Danny Stradling, and in September 1973 to Tony Engle. The former recording was included in 1998 on his Musical Traditions anthology A Broadside, and the latter in 1974 on the Topic anthology Flash Company.

Charlie Somers of Bellarea, Londonderry, sang Barbro Allen on July 18, 1969 to Hugh Shields. This recording was included in 1975 on the Leader anthologyFolk Ballads from Donegal and Derry.

Andy Cash of Co. Wexford sang Barbara Ellen in a recording made in Summer 1973 on the Musical Traditions anthology of songs of Irish Travellers in England collected by Jim Carroll and Pat Mackenzie, From Puck to Appleby. They commented in the booklet:

Probably the most widespread of all the ballads throughout the English speaking world, Barbara Allen first appeared in print in Allan Ramsay’sTea-Table Miscellany in the 18th century and has continued to make an appearance in folk song collections ever since. In William Stenhouse’s notes to the variant in The Scots Musical Museum, he wrote:

It has been a favourite ballad at every country fire-side in Scotland, time out of memory… A learned correspondent informs me that he remembers having heard the ballad frequently sung in Dumfriesshire, where, it was said, the catastrophe took place.

The enduring popularity of the ballad among country singers and a revealing insight into how it was viewed by them, was amply illustrated in an interview with American traditional singer, Jean Ritchie, who spoke about her work collecting folk songs in Ireland, Scotland and England in the early nineteen fifties. She said:

I used the song Barbara Allen as a collecting tool because everybody knew it. When I would ask people to sing me some of their old songs they would sometimes sing Does Your Mother Come from Ireland, or something about shamrocks. But if I asked if they knew Barbara Allen, immediately they knew exactly what kind of song I was talking about and they would bring out beautiful old things that matched mine and were variants of the songs that I knew in Kentucky. It was like coming home.

Andy learned this version of the ballad from an old girlfriend. He sang another version, in country and western style, complete with American accent, but he insisted that the above was “the old way of singing it”.

John Roberts and Tony Barrand sang Barbara Allen in 1974 on their album Mellow With Ale from the Horn. They commented in their liner notes:

Our version of Barbara Allen, that most venerable and best-loved of ballads, was also found fairly recently (1964) by Ewan MacColl. He, with his wife Peggy Seeger, collected it from an English gypsy, Caroline Hughes, in Dorset.

George Roberts from Devon sang Barbara Allen to Sam Richards, Tish Stubbs and Paul Wilson in between 1974 and 1976. This recording was included in 1979 on the Topic anthology Devon Tradition.

Jane Turriff sang Barbara Allen in about 1975 to Allie Munro and Tom Atkinson. This recording was included in 1996 on her Springthyme album Singin Is Ma Life.

Phoebe Smith sang Barbara Allen in a recording by Mike Yates on the 1975 anthology Songs of the Open Road; Gypsies, Travellers & Country Singers. Jon Boden credits Phoebe Smith as his source in his July 5, 2010 entry of his project A Folk Song a Day.

Johnny Doughty of Brighton, Sussex, sang Barbara Allen to Mike Yates in Summer 1976. This recording was published a year later on his Topic album Round Rye Bay for More. The liner notes commented:

The popularity of Barbara Allen, at least in the version that Johnny sings, is possibly due to its inclusion in Chappell’s Popular Music of the Olden Time of 1859. The ballad was first mentioned in Pepys’s diary when, on January 2, 1666, he wrote that the actress Mary Knipp sang “her little Scotch song of Barbary Allen”.

One theory, rather unsubstantiated, is that Barbara Allen was, in fact, Barbara Villiers, a mistress of Charles II, whilst the poet Robert Graves has suggested that Barbara was a witch destroyed by her own evil spells.

Frank Hinchliffe from Sheffield sang Barbara Allen in 1976 to Mike Yates. This recording was included in between 1987-95 on the Veteran cassette The Horkey Load Vol 2 and in 2006 on the Veteran CD compilation It Was on a Market Day—Two.

Gordeanna McCulloch sang Bawbie Allan on her 1978 Topic album Sheath and Knife.

Roy Harris sang Barbry Allen in 1979 at the Folk Festival Sidmouth.

Patsy Flynn of Magheravely, Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, sang Barbara Allen on August 4, 1980 to Keith Summers and Jenny Hicks. This recording was included in 2004 on the Musical Traditions anthology of songs from around Lough Erne’s shore in the Keith Summers Collection, The Hardy Sons of Dan.

Bill Smith of Bridgnorth, Shropshire, sang Barbara Allen in a recording made by his son Andrew Smith on July 10, 1982. It was included in 2011 on his Musical Traditions anthology A Country Life: Songs and Stories of a Shropshire Man. Rod Stradling noted in the album’s booklet:

Bill’s family were proud of the fact that songs had been collected from his grandfather by ‘A big mon from London’. When Veronica asked Bill’s mother what songs his grandfather had sung, she replied “Barbaree Aling”. “Oh, do you mean Barbara Allen?” “No, Barbaree Aling!” As this is quite a conventional—albeit very short—version, it is quite possible that Bill learned it at school.

Suzie Adams and Helen Watson sang Barbarie Ellen in 1983 on their album Songbird.

Emma Briggs of Thwaite, Suffolk, sang Barbara Allen in 1983 to John Howson. He included this recording his Veteran 1993 cassette and 2009 CD Many a Good Horseman. John Howson commented:

This is a truncated version of a very widespread ballad. […] Emma Briggs learned it from her mother, who may have learned it when she worked in service. When Emma was young she hated her mother singing it because she felt it was so depressing.

Vic Legg sang Barbara Allen on the 1994 Veteran cassette / 2000 Veteran CD of Cornish songs from the Orchard/Legg family, I’ve Come to Sing a Song. This track was also included in 2007 on the CD accompanying The Folk Handbook. Lucy Wainwright Roche sang Barbara Allen on a CD of modern recordings of traditional songs to accompany this handbook, titled Old Wine New Skins.

Incantation sang Barbara Allen in 1994 on their Cooking Vinyl CD Sergeant Early’s Dream.

Wiggy Smith sang Barbara Allen on October 9, 1994 at the Victoria pub, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, to Gwilym Davies. This recording was included in 2000 on the Musical Tradition anthology of songs from the Smith family, Band of Gold.

Frankie Armstrong sang Barbara Allen in 2000 on her Fellside CD The Garden of Love.

Sangsters sang Barbara Allen on their 2000 Greentrax CD Sharp and Sweet.

Norma Waterson sang Barbary Allen in 2000 on her third solo album, Bright Shiny Morning. She commented in her sleeve notes:

I don’t know where the tune materialised from so I think I must have made it up. I know I sang it as a child, though whether it’s from school or the family I don’t know. The song is extremely old and was said to be the favourite of Charles the Second’s mistress, Nell Gwynn.

Martin Carthy sang a very similar version called Barbara Allen on the “English” CD of Fellside’s 2003 anthology Song Links: A Celebration of English Traditional Songs and their Australian Variants. Edgar Waters commented in the liner notes:

Barbara Allen is #84 in Professor Francis J. Child’s monumental collection of ballads (The English & Scottish Popular Ballads) and probably originated in the seventeenth century. Samuel Pepys referred to it as a “little Scotch” song in 1666. Whether it is Scottish or English in origin is anybody’s guess. There are many, many English and Scottish versions. It was known in English-speaking parts of Ireland by the eighteenth century, where Oliver Goldsmith heard it sung by the family dairymaid, and it remains widely sung there, and in North America. Martin Carthy learnt his version from the singing of an English worker, Jim Wilson, recorded in a Sussex country pub in 1960. The location varies from version to version but Reading is also given in the fine version collected by Ewan MacColl from the Dorset gypsy singer, Queen Caroline Hughes in 1964.

Martin Carthy sang a somewhat different version as Barbary Ellen in 1998 on his album Signs of Life. He commented in his sleeve notes:

I think that I’ve known Barbary Ellen all my life. The song I learned was very short and gave you nothing of her anger at being treated with such disdain and how that translates to the contempt with which she treats his rather late declarations of lurve… The tune is from the Shropshire gypsy, Samson Price.

The “Australian” CD of Song Links again has a very similar version to Carthy’s sung by Cathie O’Sullivan, having the same title and both ending with the rose and briar motif.

Nic Jones sang Barbara Ellen on his 2001 CD anthology Unearthed, which is a collection of concert, club and studio performances recorded prior to 1982.

Louis Killen sang Barbara Allen in 2001 as a bonus track of the CD re-issue of The Rose in June.

June Tabor sang Barbry Ellen in 2001 on her Topic CD Rosa Mundi.

Nancy Kerr and James Fagan recorded Barbara Allen in August 2005 for their Fellside CD Strands of Gold. This video shows them at Sheffield Folk Festival in 2007:

Tom and Barbara Brown sang Barbara Allen in 2005 on their WildGoose CD Tide of Change. They commented in their liner notes:

[…] This text, one of the fullest and certainly one that gives a whole perspective to the story that is often missing in other sets, comes from the extraordinary ballad singer Cyril Piggott. The tune used here was collected by Cecil Sharp from Jane Wheller of Langport in 1904.

The Devil’s Interval sang Barbara Allen in ca. 2005 on their EP Demon Lovers, naming Queen Caroline Hughes as their source.

Sara Grey sang Barbara Allen in 2005 on her Fellside CD A Long Way from Home.

Steve Tilston sang Barbry Allen in 2005 on his CD Of Many Hands.

Jim Moray sang Barbara Allen in 2006 on his eponymous CD Jim Moray and on the single Barbara Allen. This track was also included in 2010 on his anthology A Beginner’s Guide.

Paul and Liz Davenport sang Barbary Ellen in 2008 on their Hallamshire Traditions CD Songbooks.

Alasdair Roberts sang Barbara Allen in 2010 on his CD Too Long in This Condition.

Martin Simpson sang Barbry Allen in 2011 on his Topic CD Purpose and Grace.

Steve Roud included Barbara Allen in 2012 in The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs. James Findlay sang it a year later on the accompanying Fellside CD The Liberty to Choose: A Selection of Songs from The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs.

Brian Peters and Jeff Davis sang Barbara Allen on their selection of traditional songs and music from the collection made by Cecil Sharp in the Appalachian Mountains between 1916 and 1918, Sharp’s Appalachian Harvest.

Andy Turner sang Barbara Allen as the June 1, 2013 entry of his blog A Folk Song a Week. His version is from Maud Karpeles’ The Crystal Spring and was collected by Cecil Sharp in 1923, from William Pittaway of Burford in Oxfordshire.

Lucy Farrell and the Furrow Collective used to sing Elizabeth Cronin’s version of Barbara Allen at their concerts; I saw them doing it in January 2015 in Esslingen, Germany. They recorded the ballad with Emily Portman singing lead in 2016 for their second album, Wild Hog. They commented in their liner notes:

Our version of Barbara Allen, that most popular English language ballad of them all, comes from Elizabeth Cronin, who was recorded in County Cork in the early 1950s. The first reference to the song was made by Samuel Pepys in a 1666 diary entry and it has since been widely collected throughout Britain and America. Cronin’s rendition brought the song to life for Emily when she came across it on the Good People, Take Warning CD on Topic Records. The last two verses are taken from those of a version collected by Cecil Sharp from Jim and Francis Gray on April 7, 1906 in Enmore, which is number 16 in Bronson’s collection The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads.

In many versions the ballad concludes with Barbara Allen dying of a broken heart, but this version, like Cronin’s, leaves Barbara’s fate open as she walks away from her (ex) love’s death bed through the fields and lanes, with the birds and the church bells voicing her conscience and singing “hard-hearted Barbara Allen”

Lyrics

| Elizabeth Cronin sings Barbara Allen | Shirley Collins’ Barbara Allen on The Power of the True Love Knot |

|---|---|

| It was early, early in the summertime, When the flowers were freshly springing, A young man came to the North Country, Fell in love with Barbara Allen; Fell in love with Barbara Allen. A young man came to the North Country, Fell in love with Barbara Allen. |

It was round and about last Martinmas tide When the green leaves were swelling, That young Jimmy Grove of the West Country Fell in love with Barbary Allen. |

| He fell sick, and very, very bad, And more inclined to a-dying, He wrote a letter to the old house at home To the place where she was dwelling, etc. |

He sent his man into the town To the place where she was dwelling, Says, “Will you come to my master dear, If your name is Barbary Allen?” |

| Very slowly she got up And slowly she came to him, The first words she spoke when she came there Was, “Young man, I fear you’re dying.” etc. |

Then slowly, slowly got she up And slowly came she nigh him, And all she said when there she came, “Young man, I think you’re dying.” |

| “Dying, dying, not at all,” he said, “One kiss from you would cure me.” “One kiss from me you ne’er shall see, If I thought your heart was breaking.” etc. |

“Indeed, I’m sick and very sick And shan’t get any better, Unless I gain the love of one The love of Barbary Allen.” |

| “But don’t you remember last Saturday night When the red wine you were spilling? You drank a health to the ladies there But you slighted Barbary Allen.” |

|

| And Death is printed on his face And all his heart is stealing. And again he cried as she left his side, “Hard-hoarded Barbary Allen.” |

|

| As she was a-going over the fields She heard the death-bell tolling, And every sound it seemed to sigh, “Hard-hearted Barbary Allen.” |

|

| “Oh mother, mother, make my bed, Come make it soft and narrow, Since Jimmy died for me today I shall die for him tomorrow.” |

|

| Norma Waterson’s Barbary Allen on Bright Shiny Morning |

Martin Carthy’s Barbara Allen on Song Links |

| In Reading town, where I was born, A fair maid there was a-dwelling, I fixed her up to be my bride, And her name was Barbara Allen. |

|

| Now in the first part of the year When green buds they were swelling, Young Johnny Rose on his deathbed lay For love of Barbara Allen, Allen, For love of Barbary Allen. |

It was all in the month of May, When the green leaves they were a-springing, A young man on his sick bed lay, For the love of Barbara Allen. |

| He sent his men all down to her hall To the place where she was dwelling, “For you must come to my master’s house If your name is Barbary Allen, Allen, If your name is Barbary Allen.”“For death is painted upon his face And on his heart is stealing, So come you now to comfort him If your name is Barbary Allen, Allen, If your name is Barbary Allen.”“Though death is painted upon his face And on his heart is stealing, Yet little better shall he be Though my name is Barbary Allen, Allen, Though my name is Barbary Allen.” |

And he sent his servant man To the place where she was dwelling, 𝄆Saying, “Fair maid, go to your mother’s house, If your name is Barbara Allen𝄇” |

| So slowly, slowly she’s got up And slowly’s come she nigh him, But all she said when she saw him there, “Young man, I think you’re dying.” |

So slowly, slowly she walked up, So slowly she got to him, And when she called to his bedside, She says, “Young man, you’re dying.” |

| “If on your death bed you do lie What needs the tale you’re telling? I cannot keep you from your death Though my name is Barbary Allen, Allen, Though my name is Barbary Allen.”“Oh look at my bedhead,” he cried, Oh there you’ll find it ticking: My gold watch and my gold chain I’ll leave to Barbary Allen, Allen, I’ll leave to Barbary Allen.”“Oh look at my bed foot,” he cried, And there you’ll see them lying: Bloody sheets and bloody shirts, I’ve sweated for you, Allen.” |

“Oh nothing would help what’s in your fate, Oh daughter, take it from me, I cannot save you from the grave, So farewell dearest Johnny.” |

| And as she walked all across the field She’s heard the death bell knelling, And every stroke that death bell gave Cried, “Woe be to you, Allen.” |

As she was walking through the field She heard the bells a-ringing, And as they rang, they seemed to say, “Hard-hearted Barbara Allen.” |

| And then she’s turned herself around, She saw his corpse a-coming, “Lie down, lie down your weary load Till I get to gaze upon him.” |

And she was walking through the street She saw his corpse a-coming, 𝄆“You little hearts come set him down, And let me gaze all on him.”𝄇 |

| When he’s dead and laid in his grave Her heart was struck with sorrow, “Oh mother, mother make my bed For I must die tomorrow.” |

The more she looked, the more she laughed, And farther she got to him, And her friends cried out for shame, “Hard-hearted Barbara Allen.” |

| “Hard-hearted was I him to slight He who loved me dearly, Oh had I been more kind to him When he was alive and near me, near me, When he was alive and near me.” |

“Hard-hearted creature sure I was To the one that loved me dearly, 𝄆I wish I had more kinder been, In the time of life was near me.”𝄇 |

| And she upon her death bed lay, Bed to be buried by him. And she’s repented of the day That e’er she did deny him. |

It was he that died was today, She died on the morrow, 𝄆It was he that died for love, And she has died for sorrow.𝄇 |

| Martin Carthy’s Barbary Ellen on Signs of Life |

Cathy O’Sullivan’s Barbary Ellen on Song Links |

| All in the third part of the year When green leaves they were falling, Young Johnny Rose, all down from the war, Fell in love with Barbary Ellen. |

In Dublin I was reared and born, In Dublin I was dwelling. I fell in love with a dark eyed girl And her name was Barbary Ellen. |

| He sent his men down to the town To the place where she was dwelling, Saying, “Lady, come quick and come very quick If your name be Barbary Ellen.” |

He sent his servant to her room, To the place where she was dwelling, Saying, “Haste unto my master’s room If your name be Barbary Ellen.” |

| So slowly, slowly she rose up, So slowly she put on her, So slowly come to his bedside And so slowly she looked upon him.“You’re lying low, young man,” she cries, “And death is with you dealing. No the better for me you never shall be Though your heart’s blood were spilling.”“Oh look at my bedhead,” he cries, “And there you’ll find it ticking: My gold watch and my gold chain, I bestow them to you, my Ellen.”“Oh look at my bed foot,” he cries, “And there you will find them lying: Bloody sheets and bloody shirts, I swept them for you, my Ellen.” |

‘Twas slowly, slowly she put on her clothes And slowly she walked to him, She pulled the curtains from round of his head Saying, “Young man, you are dying.” |

| “Tell me, do you mind the time, ” she cries, “All in the tavern swilling? You made the health of all round the place But never for your love Ellen.” |

“Don’t you remember last Saturday night Whilst drinking at the Royal? You drank the health of all fair maids But you slighted Barbary Ellen”“Oh it’s well I remember last Saturday night Whilst drinking at the Royal, I drunk the health of all fair maids But my trust to Barbary Ellen.” |

| She walked over yon garden field, She heard the dead bell knelling. And every stroke that the dead bell gave It cried, “Woe be to you now, Ellen.”She walked over yon garden field, She saw his corpse a-coming, “Lay down, lay down, your weary load Until I get to look upon him.”She lifted the lid from off the corpse, She bursted out with laughing. And all of his friends that stood round about, They cried, “Woe be to you now, Ellen.” |

|

| She come home to her father’s house, “Make my bed long and narrow, For young Johnny Rose died for me today And I must die tomorrow.” |

“Oh mother, mother, make by bed, Oh make it soft and narrow. For William died of love today And I shall die of sorrow.”“Oh father, father, dig my grave, Oh dig it deep and narrow. For William died for me today And I shall die tomorrow.” |

| They buried her all in the churchyard, They buried him in the choir. And out of him there grew a red rose And out of her a briar. |

A rose grew from fair William’s heart, From Barbary Ellen’s a briar, They grew and grew to the top of the church Till they couldn’t grow any higher. |

| They grew and they grew all in the churchyard Till they could grow no higher. They twisted and twined themselves in a knot As the rose growed all round the briar. |

They grew and grew to the top of the church Till they couldn’t grow any higher, And at the top they formed a knot, 𝄆 The rose wrapped round the briar. 𝄇 |

Acknowledgements and Links

See also the Mudcat Café thread Origins: Barbara Allen.

Gary Gillard transcribed the texts from Bright Shiny Morning and Signs of Life.

Performances, Workshops,

Resources & Recordings

The American Folk Experience is dedicated to collecting and curating the most enduring songs from our musical heritage. Every performance and workshop is a celebration and exploration of the timeless songs and stories that have shaped and formed the musical history of America. John Fitzsimmons has been singing and performing these gems of the past for the past forty years, and he brings a folksy warmth, humor and massive repertoire of songs to any occasion.

Festivals & Celebrations

Coffeehouses

School Assemblies

Library Presentations

Songwriting Workshops

Artist in Residence

House Concerts

Pub Singing

Irish & Celtic Performances

Poetry Readings

Campfires

Music Lessons

Senior Centers

Voiceovers & Recording

““Beneath the friendly charisma is the heart of a purist gently leading us from the songs of our lives to the timeless traditional songs he knows so well…”

Join Fitz

at The Colonial Inn

“The Nobel Laureate of New England Pub Music…”

On the Green, in Concord, MA

Every Thursday Night

for over thirty years…

“A Song Singing, Word Slinging, Story Swapping,

Ballad Mongering, Folksinger, Teacher, & Poet…”

Fitz’s Recordings

& Writings

Songs, poems, essays, reflections and ramblings of a folksinger, traveler, teacher, poet and thinker…

Download for free from the iTunes Bookstore

“A Master of Folk…”

Fitz’s now classic recording of original songs and poetry…

Download from the iTunes Music Store

“A Masterful weaver of song whose deep, resonant voice rivals the best of his genre…”

“2003: Best Children’s Music Recording of the Year…”

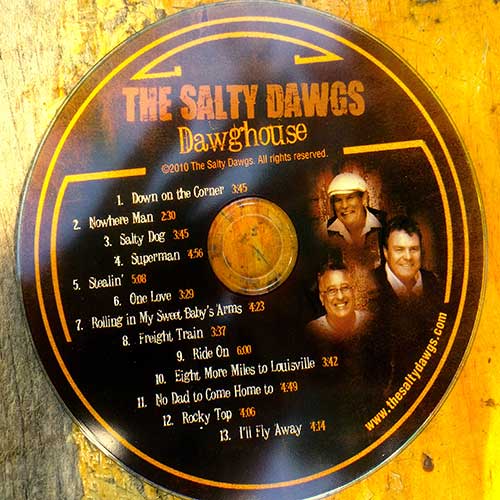

Fitz & The Salty Dawgs

Amazing music, good times and good friends…

TheCraftedWord.org

Writing help

when you need it…

“When the eyes rest on the soul…that’s Fitzy…”

0 Comments