Little Musgrave & Lady Barnard

Child Ballad #81

On a day, on a day, on a bright holiday as many there be in the year

When Little Musgrave to the church did go, god’s holy word to hear.

He went and he stood all at the church door; he watched the priest at his mass.

But he had more mind of the fair women than he had of Our Lady’s grace.

For some of them were clad in the green and some were clad in the pall,

And in and come Lord Barnard’s wife, the fairest among them all.

She cast her eye on Little Musgrave, full bright as the summer sun,

And then and thought this Little Musgrave, this lady’s heart I have won.

Says she, “I have loved thee, Little Musgrave, full long and many’s the day.”

“So have I loved, lady fair, yet never a word durst I say.”

“Oh I have a bower at Bucklesfordberry all daintily painted white

And if thou’d went thither, thou Little Musgrave, thou’s lie in my arms all this night.”

Says he, “I thank thee, lady fair, this kindness thou showest to me

And this night will I to Bucklesfordberry, all night for to lay with thee.”

When he heard that, her little foot page all by her foot as he run

He says, “Although I am my lady’s page, yet am I Lord Barnard’s man.

My Lord Barnard shall know of this, whether I do sink or do swim.”

And ever where the bridges were broke, he laid to his breast and he swum.

“Oh sleep thou wake, thou Lord Barnard, as thou art a man of life.

For Little Musgrave is at Bucklesfordberry in bed with thine own wedded wife.”

“Oh if this be true, thou little foot page, this thing that thou tellest to me

Then all my land in Bucklesfordberry freely I give it to thee.

But if this be a lie, thou little foot page, this thing that thou tellest to me

Then from the highest tree in Bucklesfordberry high hanged thou shalt be.”

And he called to him his merry men, all by one by two by three,

Says, “this night must I to Bucklesfordberry, for never had I greater need.”

And he called to him his stable boy, “Go saddle me me milk-white steed.”

And he’s trampled o’er them green mossy banks, till his horse’s hooves did bleed.

And some men whistled, and some men sang, and some these words did say

Whene’er my Lord Barnard’s horn blew, “Away, Musgrave away.”

“Methinks I hear the thistle cock, methinks I hear the jay,

Methinks I hear the Lord Barnard’s horn, and I wish I were away.”

“Lie still, lie still, thou Little Musgrave, come cuddle me from the cold,

For tis nothing but a shepherd boy, adriving his sheep to the fold.

Is not thy hawk sat upon his perch, they steed eats oats and hay,

And thou with a fair maid in thy arms and would’st thou be away.”

With that my Lord Barnard come to the door and he lit upon a stone,

And he’s drawn out three silver keys and he’s opened the doors each one.

And he’s lifted up the green coverlet and he’s lifted up the sheet:

“How now, how now, thou Little Musgrave, dost find my lady sweet?”

“I find her sweet,” says Little Musgrave, “The more tis to my pain

For I would give three hundred pounds, that I was on yonder plain.”

“Rise up, rise up,” thou Little Musgrave, “and put thy clothes on

For never shall they say in my own country i slew a naked man.

Oh I have two swords in one scabbard, full dearly they cost my purse.

And thou shall have the best of them, and I shall have the worst.”

Now the very first blow Little Musgrave struck, he hurt Lord Barnard sore;

But the very first blow Lord Barnard struck, little Musgrave ne’er struck more.

Then up and spoke his lady fair, from the bed whereon she lay,

She says, “Although thou art dead, thou Little Musgrave, yet for thee will I pray.

I will wish well to thy soul, as long as I have life,

Yet will I not for thee Lord Barnard, though I am your own wedded wife.”

Oh he’s cut the paps from off her breast, great pity it was to see

How the drops of this lady’s heart’s blood came a-trickling down her knee.

“Oh woe be to ye, me merry men, all you were ne’er born for my good.

Why did you not offer to stay my hand, when you see me grow so mad?”

“A grave, a grave,” Lord Barnard cried, “to put these lovers in.

But lay my lady on the upper hand, she was the chiefest of her kin.”

(as sung by Martin Carthy)

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I am indebted to the many friends who share my love of traditional songs and to the many scholars whose works are too many to include here. I am also incredibly grateful to the collector’s curators and collators of Wikipedia, Mudcat.org, MainlyNorfolk.info, and TheContemplator.com for their wise, thorough and informative contributions to the study of folk music.

I share their research on my site with humility, thanks, and gratitude. Please cite their work accordingly with your own research. If you have any research or sites you would like to share on this site, please post in the comment box. Thanks!

Contents

| Matty Groves | |

|---|---|

| English folk song | |

"A lamentable ballad of the little Musgrove". A seventeenth-century broadside held in the Bodleian Library. | |

| Catalogue | Child Ballad 81 Roud Folk Song Index 52 |

| Genre | Ballad |

| Language | English |

| Performed | First attested in writing in 1613 |

| Published | Earliest surviving broadside dated to before 1675 |

| Also known by several other names | |

"Matty Groves", also known as "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard" or "Little Musgrave", is a ballad probably originating in Northern England that describes an adulterous tryst between a young man and a noblewoman that is ended when the woman's husband discovers and kills them. It is listed as Child ballad number 81 and number 52 in the Roud Folk Song Index.[1][2] This song exists in many textual variants and has several variant names. The song dates to at least 1613, and under the title Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard is one of the Child ballads collected by 19th-century American scholar Francis James Child.

Synopsis

Little Musgrave (or Matty Groves, Little Matthew Grew and other variations) goes to church on a holy day either "the holy word to hear" or "to see fair ladies there". He sees Lord Barnard's wife, the fairest lady there, and realises that she is attracted to him. She invites him to spend the night with her, and he agrees when she tells him her husband is away from home. Her page overhears the conversation and goes to find Lord Barnard (Arlen, Daniel, Arnold, Donald, Darnell, Darlington) and tells him that Musgrave is in bed with his wife. Lord Barnard promises the page a large reward if he is telling the truth and to hang him if he is lying. Lord Barnard and his men ride to his home, where he surprises the lovers in bed. Lord Barnard tells Musgrave to dress because he doesn't want to be accused of killing a naked man. Musgrave says he dare not because he has no weapon, and Lord Barnard gives him the better of two swords. In the subsequent duel Little Musgrave wounds Lord Barnard, who then kills him. (However, in one version "Magrove" instead runs away, naked but alive.)[3][4]

Lord Barnard then asks his wife whether she still prefers Little Musgrave to him and when she says she would prefer a kiss from the dead man's lips to her husband and all his kin, he kills her. He then says he regrets what he has done and orders the lovers to be buried in a single grave, with the lady at the top because "she came of the better kin". In some versions Barnard is hanged, or kills himself, or finds his own infant son dead in his wife's body. Many versions omit one or more parts of the story.[1]

It has been speculated that the original names of the characters, Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard, come from place names in the north of England (specifically Little Musgrave in Westmorland and Barnard Castle in County Durham). The place name "Bucklesfordbury", found in both English and American versions of the song, is of uncertain origin.

Some versions of the ballad include elements of an alba, a poetic form in which lovers part after spending a night together.

Early printed versions

There are few broadside versions. There are three different printings in the Bodleian Library's Broadside Ballads Online, all dating from the second half of the seventeenth century. One, The lamentable Ditty of the little Mousgrove, and the Lady Barnet from the collection of Anthony Wood, has a handwritten note by Wood on the reverse stating that "the protagonists were alive in 1543".[5][6][7][8]

Below are the first four verses as written in a version published in 1658.

As it fell one holy-day, hay downe,

As many be in the yeare,

When young men and maids

Together did goe,

Their Mattins and Masse to heare,

Little Musgrave came to the church dore,

The Preist was at private Masse

But he had more minde of the faire women;

Then he had of our lady grace

The one of them was clad in green

Another was clad in pale,

And then came in my lord Bernards wife

The fairest amonst them all;

She cast an eye on little Musgrave

As bright as the summer sun,

And then bethought this little Musgrave

This lady's heart have I woonn.[9][10]

Traditional recordings

It seems that the ballad had largely died out in the British Isles by the time folklorists began collecting songs. Cecil Sharp collected a version from an Agnes Collins in London in 1908, the only known version to have been collected in England.[11][12] James Madison Carpenter recorded some Scottish versions, probably in the early 1930s, which can be heard on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library website.[13][14] The Scottish singer Jeannie Robertson was recorded on separate occasions singing a traditional version of the song entitled "Matty Groves" in the late 1950s by Alan Lomax,[15] Peter Kennedy[16] and Hamish Henderson.[17] However, according to the Tobar an Dualchais website, Robertson may have learned her version from Johnny Wells and Sandy Paton, Paton being an American singer and folk song collector.[18]

Dozens of traditional versions of the ballad were recorded in the Appalachian region. Jean Bell Thomas recorded Green Maggard singing "Lord Daniel" in Ashland, Kentucky, in 1934, which was released on the anthology 'Kentucky Mountain Music' Yazoo YA 2200.[19] Bascom Lamar Lunsford was recorded singing a version called "Lord Daniel's Wife" in 1935.[20] Samuel Harmon, known as "Uncle" Sam Harmon, was recorded by Herbert Halpert in Maryville, Tennessee, in 1939 singing a traditional version.[21] The influential Appalachian folk singer Jean Ritchie had her family version of the ballad, called "Little Musgrave", recorded by Alan Lomax in 1949,[22] who made a reel-to-reel recording of it in his apartment in Greenwich Village;[23] she later released a version on her album Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition (1961).[24] In August 1963, John Cohen recorded Dillard Chandler singing "Mathie Groves" in Sodom, North Carolina,[25] whilst Nimrod Workman, another Appalachian singer, had a traditional version of the song recorded in 1974.[26]

The folklorist Helen Hartness Flanders recorded many versions in New England in the 1930s and 40s,[27] all of which can be heard online in the Flanders Ballad Collection.[28]

Canadian folklorists such as Helen Creighton, Kenneth Peacock and Edith Fowke recorded about a dozen versions in Canada, mostly in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.[29]

A number of songs and tales collected in the Caribbean are based on, or refer to, the ballad.[30][31][32][33]

Textual variants and related ballads

| Variant | Lord/Lady's surname | Lover | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Old ballad of Little Musgrave and the Lady Barnard | Barnard | Little Musgrave | This version has the foot-page |

| Mattie Groves | Arlen | Little Mattie Groves | [34] |

| Matty Groves | Darnell | Matty Groves | [35] |

Some of the versions of the song subsequently recorded differ from Child's catalogued version.[36] The earliest published version appeared in 1658 (see Literature section below). A copy was also printed on a broadside by Henry Gosson, who is said to have printed between 1607 and 1641.[34] Some variation occurs in where Matty is first seen; sometimes at church, sometimes playing ball.

Matty Groves also shares some mid-song stanzas with the ballad "Fair Margaret and Sweet William" (Child 74, Roud 253).[37][38]

Other names for the ballad:

- Based on the lover

- Little Sir Grove

- Little Massgrove

- Matthy Groves

- Wee Messgrove

- Little Musgrave

- Young Musgrave

- Little Mushiegrove

- Based on the lord

- Lord Aaron

- Lord Arlen

- Lord Arnold

- Lord Barlibas

- Lord Barnabas

- Lord Barnaby

- Lord Barnard

- Lord Barnett

- Lord Bengwill

- Lord Darlen

- Lord Darnell

- Lord Donald

- Based on a combination of names

Literature

The earliest known reference to the ballad is in Beaumont and Fletcher's 1613 play The Knight of the Burning Pestle:

And some they whistled, and some they sung,

Hey, down, down!

And some did loudly say,

Ever as the Lord Barnet's horn blew,

Away, Musgrave, away![39]

Al Hine's 1961 novel Lord Love a Duck opens and closes with excerpts from the ballad, and borrows the names Musgrave and Barnard for two characters.[40]

Deborah Grabien's third book in the Haunted Ballad series, Matty Groves (2005), puts a different spin on the ballad.[41]

Commercial recordings

Versions of some performers could be mentioned as the most notable or successful, including those by Jean Ritchie[42] or Martin Carthy.[43]

| Year | Release (Album / "Single") | Performer | Variant | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | John Jacob Niles Sings American Folk Songs | John Jacob Niles | Little Mattie Groves | |

| 1958 | Shep Ginandes Sings Folk Songs | Shep Ginandes | Mattie Groves | [44] |

| 1960 | British Traditional Ballads in the Southern Mountains, Volume 2 | Jean Ritchie | Little Musgrave | |

| 1962 | Joan Baez in Concert | Joan Baez | Matty Groves | |

| 1964 | Introducing the Beers Family | Beers Family | Mattie Groves | |

| 1966 | Home Again! | Doc Watson | Matty Groves | |

| 1969 | Liege & Lief | Fairport Convention | Matty Groves | Set to the tune of the otherwise unrelated Appalachian song "Shady Grove"; this hybrid version has therefore entered other performers' repertoires over time (the frequency of this as well as the similarity of the names has led to the erroneous assumption that "Shady Grove" is directly descended from "Matty Groves"). Several live recordings also.[citation needed] |

| 1969 | Prince Heathen | Martin Carthy | Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard | |

| 1970 | Ballads and Songs | Nic Jones | Little Musgrave | |

| 1976 | Christy Moore | Christy Moore | Little Musgrave | Set to a tune Andy Irvine learnt from Nic Jones[45] |

| 1977 | Never Set the Cat on Fire | Frank Hayes | Like a Lamb to the Slaughter | Done as a parody talking blues version |

| 1980 | The Woman I Loved So Well | Planxty | Little Musgrave | |

| 1990 | Masque | Paul Roland | Matty Groves | |

| 1992 | Just Gimme Somethin' I'm Used To | Norman and Nancy Blake | Little Matty Groves | |

| 1992 | Out Standing in a Field | The Makem Brother and Brian Sullivan | Matty Groves | |

| 1993 | In Good King Arthur's Day | Graham Dodsworth | Little Musgrave | |

| 1994 | You Could Be the Meadow | Eden Burning | ||

| 1995 | Live at the Mineshaft Tavern | ThaMuseMeant | ||

| 1997 | On and On | Fiddler's Green | Matty Groves | |

| 1994 | You Could Be the Meadow | Eden Burning | ||

| 1999 | Trad Arr Jones | John Wesley Harding | Little Musgrave | |

| 2000 | Hepsankeikka | Tarujen Saari | Kaunis neito | (In Finnish) |

| 2001 | Listen, Listen | Continental Drifters | Matty Groves | |

| 2002 | Ralph Stanley | Ralph Stanley | Little Mathie Grove | |

| 2004 | Live 2004 | Planxty | Little Musgrave | |

| 2005 | Dark Holler: Old Love Songs and Ballads | Dillard Chandler | Mathie Grove | Acapella Appalachian.[46] |

| 2005 | De Andere Kust | Kadril | Matty Groves | |

| 2007 | Season of the Witch | The Strangelings | Matty Groves | |

| 2007 | Prodigal Son | Martin Simpson | Little Musgrave | |

| 2008 | The Peacemaker's Chauffeur | Jason Wilson | Matty Groves | Reggae version, featuring Dave Swarbrick & Brownman Ali |

| 2009 | Folk Songs | James Yorkston and the Big Eyes Family Players | Little Musgrave | |

| 2009 | Alela & Alina | Alela Diane featuring Alina Hardin | Matty Groves, Lord Arland | |

| 2009 | Tales From the Crow Man | Damh the Bard | Matty Groves | |

| 2009 | Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers & Bastards | Tom Waits | Mathie Grove | |

| 2010 | Sweet Joan | Sherwood | Matty Groves | (In Russian) |

| 2011 | Birds' Advice | Elizabeth Laprelle | Mathey Groves | |

| 2011 | "Little Musgrave" | The Musgraves | Little Musgrave | YouTube video recorded to explain the band's name |

| 2011 | In Silence | Marc Carroll | Matty Groves | |

| 2012 | Retrospective | The Kennedys | Matty Groves | |

| 2013 | The Irish Connection 2 | Johnny Logan | ||

| 2013 | Fugitives | Moriarty | Matty Groves | |

| 2019 | Dark Turn of Mind | Iona Fyfe | Little Musgrave | Scots folklore variant written in Scottish English[47] |

| 2019 | Návrat krále | Asonance | Matty Groves | (In Czech) |

| 2024 | Kleptocracy | Ferocious Dog | Matty Groves |

Film and television

Film

In the film Songcatcher (2000), the song is performed by Emmy Rossum and Janet McTeer.

Television

In season 5 episode 2, "Gently with Class" (2012), of the British television series Inspector George Gently, the song is performed by Ebony Buckle, playing the role of singer Ellen Mallam in that episode, singing it as "Matty Groves".

Musical variants

In 1943, the English composer Benjamin Britten used this folk song as the basis of a choral piece entitled "The Ballad of Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard".[48]

"The Big Musgrave", a parody by the Kipper Family, appears on their 1988 LP Fresh Yesterday. The hero in this version is called Big Fatty Groves.[49]

Frank Hayes created a talking blues version of Matty Groves called "Like a Lamb to the Slaughter," which won the 1994 Pegasus Award for "Best Risqué Song."

"Maggie Gove", a parody by UK comedy folk-band The Bar-Steward Sons of Val Doonican, appears on their 2022 album Rugh & Ryf. The anti-hero in this version is Margaret Gove, a folk-singer of traditional broadside ballads.[50] The song features guest appearances from Dave Pegg and Dave Mattacks from Fairport Convention.[citation needed]

See also

The previous and next Child Ballads:

References

- ^ a b Francis James Child (13 November 2012). The English and Scottish Popular Ballads Vol. 2. Courier Corporation. p. 243. ISBN 9780486152837. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Matty Groves". vwml.org. English Folk Dance and Song Society / Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Katherine Jackson French: Kentucky's Forgotten Ballad Collector". Oldtime Central. 23 June 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ a b DiSavino, Elizabeth (2020). Katherine Jackson French: Kentucky's Forgotten Ballad Collector. University Press of Kentucky.

- ^ "A Lamentable Ballad of Little Musgrave, and the Lady Barnet". ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Bodleian Ballads Online. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "The lamentable Ditty of little Mousgrove, and the Lady Barnet". ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Bodleian Ballads Online. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "[A] Lamentable Ballad of the Little Musgrove, and the Lady Barnet". ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Bodleian Ballads Online. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Ballads Online". ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ "Child Ballads - Lyrics". 71.174.62.16. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Mennes, John; Smith, James, eds. (1658). . . London: R. Pollard, N. Brooks, and T. Dring. pp. 174–175.

- ^ "Little Musgrave (Cecil Sharp Manuscript Collection (at Clare College, Cambridge) CJS2/9/1553)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Musgrave (Cecil Sharp Manuscript Collection (at Clare College, Cambridge) CJS2/10/1691)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Musgrove (VWML Song Index SN18800)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Musgrove (VWML Song Index SN19227)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Lord Donald (Roud Folksong Index S341660)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard (Roud Folksong Index S242813)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard (Roud Folksong Index S437094)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Jeannie Robertson singing "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard", recorded in Scotland by Hamish Henderson (September 1960). "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard". www.tobarandualchais.co.uk (Reel-to-reel). Scotland: Tobar an Dualchais/Kist o' Riches. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Roud Folksong Index (S243414) - "Lord Daniel"". vwml.org. English Folk Dance and Song Society / Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Lord Daniel's Wife (Roud Folksong Index S262168)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Matthew Grove (Roud Folksong Index S261972)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Little Musgrave (Roud Folksong Index S341705)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Jean Ritchie singing "Little Musgrave" in Alan Lomax's apartment, 3rd Street, Greenwich Village, New York City (New York), United States (2 June 1949). "Little Musgrave". research.culturalequity.org (Reel-to-reel). New York: Association for Cultural Equity. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Jean Ritchie: Ballads from her Appalachian Family Tradition". Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Mathie Groves (Roud Folksong Index S373182)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Lord Daniel (Roud Folksong Index S401586)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "VWML: rn52 sound usa flanders". Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

- ^ "Helen Hartness Flanders Ballad Collection : Free Audio : Free Download, Borrow and Streaming : Internet Archive". archive.org. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "rn52 sound canada". Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

- ^ "Little Musgrove- Maroons (JM) pre1924 Beckwith C". bluegrassmessengers.com. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Garoleen- Joseph (St Vincent) 1966 Abrahams C". bluegrassmessengers.com. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Matty Glow- Antoine (St Vincent) 1966 Abrahams B". bluegrassmessengers.com. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Little Musgrove- Forbes (JM) pre1924 Beckwith A, B". bluegrassmessengers.com. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Mattie Groves". contemplator.com. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "The Celtic Lyrics Collection - Lyrics". celtic-lyrics.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Francis James Child (13 November 2012). The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Courier Corporation. p. 243. ISBN 9780486152837. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Keefer, Jane (2011). "Fair Margaret and Sweet William". Ibiblio. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ Niles, John Jacob (1961). The Ballad Book of John Jacob Niles. Bramhall House, New York. pp. 159–161, 194–197.

- ^ "The Knight of the Burning Pestle, by Beaumont & Fletcher, edited by F. W. Moorman". gutenberg.ca.

- ^ Hine, Al (1961). Lord Love a Duck. Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 2, 367. Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via babel.hathitrust.org.

- ^ Grabien, Deborah (2005). Matty Groves. Minotaur Books. ISBN 0-312-33389-7. Retrieved 28 February 2016 – via amazon.com.

- ^ Midwest Folklore. Indiana University. 1954.

- ^ The Gramophone. C. Mackenzie. 1969.

- ^ ""Mattie Groves" by Shep Ginandes". secondhandsongs.com. SecondHandSongs. 1958. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

- ^ Smithsonian Folkways – SFW 40170

- ^ Fyfe, Iona [in Scots] (1 January 2019). "Little Musgrave". Dark Turn of Mind. Bandcamp (Media notes). Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Stone, Kurt (1 October 1965). "Reviews of Records". The Musical Quarterly. LI (4): 722–724. doi:10.1093/mq/LI.4.722.

- ^ "Big Musgrave". The Kipper Family. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ "RUGH & RYF | LYRICS". The Bar-Steward Sons of Val Doonican. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

External links

- "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard". Francis James Child. traditionalmusic.co.uk

- "Matty Groves". Fairport Convention. celtic-lyrics.com.

- "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard". sacred-texts.com

- "Mattie Groves". contemplator.com

| Preceded by 51 |

List of Roud folk songs 52 |

Succeeded by 53 |

| Preceded by 80 |

List of the Child Ballads 81 |

Succeeded by 82 |

Source: Mainly Norfolk

Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard / Matty Groves

[ Roud 52 ; Child 81 ; Ballad Index C081 ; Bodleian Roud 52 ; trad.]

Jeannie Robertson sang Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard in Aberdeen in 1958 to Peter Kennedy. This recording was included in 2000 on the extended Rounder re-issue of Volume 4 of The Folk Songs of Britain, Classic Ballads of Britain and Ireland Volume 1.

Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl sang Matty Groves in 1961 on their Folkways album of American, Scots and English folksongs, Two-Way Trip. They commented in the album’s booklet:

This extremely popular traditional ballad is of considerable antiquity and a great number of different versions have been collected. According to Chappell, the first broadside version was published as early as 1607 by Henry Gosson. Child prints 14 texts. The version here is a collation of American and Nova Scotian variants.

Hedy West sang Little Matty Groves in 1965 on her Topic album of Appalachian ballads, Pretty Saro. She commented in her sleeve notes:

Little Matty Groves (Litte Musgrave and Lady Barnard) was quoted in Beaumont and Fletcher’s Knight of the Burning Pestle, written about 1611. Both Grandma and Gus’ wife Jane sing a fragment of Little Matty Groves that breaks off before Lord Arnold discovers his wife and Matty Groves in bed together. Neither Grandma nor Jane ever knew more of the ballad. An earlier singer has fragmented the song either by censoring or forgetting. This family version is completed with another American text collected by Vance Randolph. I find the ballad intensely tragic because its characters knowingly pursue ruin by insisting on unbending truthfulness.

Matty Groves is one of Fairport Convention’s best known songs. They recorded it lots of times both with and without Sandy Denny: The first (and most famous) version with Sandy appeared in 1969 on Liege and Lief where the line-up is Denny / Hutchings / Mattacks / Nicol / Swarbrick / Thompson. This version also appears on The History of Fairport Convention, on the double CD compilation Meet on the Ledge: The Classic Years 1967-1975 and on the Island samplers Island Life: 25 Years of Island Records and Folk Routes. The tune used as the basis for the instrumental at the end comes from a banjo piece by Eddie West, and was also used by Martin Carthy in his version of the song Famous Flower of Serving Men.

The second version with Sandy was recorded on January 26, 1974 at the Sydney Opera House, Australia, with Denny / Donahue / Lucas / Mattacks / Pegg / Swarbrick. It was released on Fairport’s Live album. Two more performances from Ebbets Field, Denver, Colorado of May 1974 were published in 2002 onBefore the Moon.

A Danish TV broadcast from November 1969 is not available.

Fairport Convention’s first version without Sandy Denny appeared on Live at the L.A. Troubadour, recorded in 1970 with Mattacks / Nicol / Pegg / Swarbrick / Thompson, and the second version is on the 1979 live album Farewell, Farewell. The third version without Sandy was recorded for the 1987 live-in-the-studio album In Real Time, as part of the “Big Three Medley”; this version also appeared in the video It All Comes ‘Round Again.

And this Fairport perennial is treated to yet another arrangements, e.g. live at Cropredy 1983, which was released on the cassette The Boot—1983 Fairport Reunion, in the 1990 video Live Legends, and on the 25th Anniversary Concert CD (1992).

A specially multi-version compiled of several Matty Groves versions—among them Sandy in the classic Liege and Lief rendering—is on the Fairport unConventioNal 4CD set. It is framed by excerpts from “The Matty Groves Crime Report” which began Fairport’s set at Cropredy in 1998.

Martin Carthy sang Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard unaccompanied on his 1969 album with Dave Swarbrick, Prince Heathen. He commented in the album’s sleeve notes:

The story speaks for itself and really needs nothing written about it at all. The tune I pinched from a version of the Holy Well.

Nic Jones sang Little Musgrave in 1970 on his first solo album, Ballads and Songs. He commented in his album sleeve notes:

Three very common ballads are included in this record: Sir Patrick Spens, The Outlandish Knight and Little Musgrave. All three are well-known to anyone with a knowledge of balladry, as they are well represented in most ballad collections. … Musgrave‘s tune is more a creation of my one than anything else, although the bulk of it is based on an American variant of the same ballad, entitled Little Matty Groves.

John Wesley Harding covered Nic Jones’s version in 1999 on his CD Trad Arr Jones. See also Karen Myer’s blog analysing Nic Jones’ song.

Frankie Armstrong sang Little Musgrave in 1975 on her Topic album Songs and Ballads. A.L. Lloyd commented in the sleeve notes:

Many people connect the events of this ballad with the district of Barnard Castle, Co. Durham. Perhaps. Anyway, the song tells a powerful story that unrolls like a film scenario, exterior, interior, distant shots that cut to close-up. Frankie Armstrong finds this exceptionally powerful: the wife trapped in a marriage probably not of her own choosing; the lover whose ardour outweighs his caution; the husband who has to be seen to do the right thing and who desperately tries to avoid the tragic outcome. The words of this version are substantially those obtained by William Motherwell “from the recitation of Mrs. McConechie, Kilmarnock” at the start of the nineteenth century. A bit of the ballad is quoted in Beaumont and Fletcher’s Knight of the Burning Pestle (1611), and it was printed on broadsides several times in the seventeenth century but by the mid-nineteenth century it was rarely reported; such a good song, one wonders why; especially as it remained popular among American folk singers.

Christy Moore sang Little Musgrave in 1980 on Planxty’s Tara album The Woman I Loved So Well. He commented in the album’s sleeve notes:

I was first drawn to this song by its length. The first verse appealed to me because I too went to Mass to look at girls. I collected it in a book which had no music but I was lucky to collect a tune from Nic Jones album discovered on a field trip through Liam O’Flynn’s flat. I first heard the adjoining tune (Paddy Fahey’s Reel) in a dressing room in Germany when, having just died the death, Matt played to us and made me forget where I was for 3 minutes 23 seconds.

John Wright sang Matty Groves in 1997 on the Fellside anthology Ballads. Paul Adams commented in the liner notes:

Adultery, lust, an unfaithful wife, revenge, crime of passion, loyalty—modern tabloids would have a field day with this story. Matty has ideas above his station. He also is one of the earliest recorded “toy boys.” This is another well travelled ballad which got a new lease of life a few years ago when it was recorded by the folk rock band, Fairport Convention. John has two versions, one from the great Scots ballad singer Jeannie Robertson via Lorna Campbell and the other from the Appalachian singer, Hedy West. Unable to choose John extracted the best elements of each and created this version. What makes the story classic tragedy is the way in which all principal characters progress inexorably to the inevitable conclusion.

Isla St Clair sang Matty Groves in 2000 on her CD Royal Lovers & Scandals.

The Continental Drifters covered Fairport Convention’s version of Matty Groves in 2001 on their album Listen, Listen. and Linde Nijland sang it in 2003 on her CD Linde Nijland Sings Sandy Denny.

Martin Simpson sang Little Musgrave in 2007 on his Topic CD and DVD Prodigal Son. He commented in his liner notes:

When learning a version of a big ballad, there are often many choices to be made. There may be several recorded versions that you like, or a great tune with a dubious text, or vice versa, or no tune and little text. You might have to write or re-build and collate. In the case of Little Musgrave I had spent several years reading, listening and considering, when one day I remembered Nic Jones’ recorded version on his first album, Ballads and Songs. I didn’t go back and listen, I just started to play.

This video shows Martin Simpson at Bournemouth Folk Club, Centre Stage, Dorset, UK, on March 8, 2009:

James Yorkston & The Big Eyes Family Players sang Little Musgrave in 2009 on their CD Folk Songs.

Jon Boden sang Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard as the May 30, 2011 entry of his project A Folk Song a Day.

Gudrun Walther sang Planxty’s version of Little Musgrave on Cara’s 2016 CD Yet We Sing.

Lyrics

Sandy Denny sings Matty Groves

A holiday, a holiday, and the first one of the year.

Lord Darnell’s wife came into church, the gospel for to hear.

And when the meeting it was done, she cast her eyes about,

And there she saw little Matty Groves, walking in the crowd.

“Come home with me, little Matty Groves, come home with me tonight.

Come home with me, little Matty Groves, and sleep with me till light.”

“Oh, I can’t come home, I won’t come home and sleep with you tonight,

By the rings on your fingers I can tell you are Lord Darnell’s wife.”

“What if I am Lord Darnell’s wife? Lord Darnell’s not at home.

For he is out in the far cornfields, bringing the yearlings home.”

And a servant who was standing by and hearing what was said,

He swore Lord Darnell he would know before the sun would set.

And in his hurry to carry the news, he bent his breast and ran,

And when he came to the broad mill stream, he took off his shoes and swam.

Little Matty Groves, he lay down and took a little sleep.

When he awoke, Lord Darnell he was standing at his feet.

Saying “How do you like my feather bed? And how do you like my sheets?

How do you like my lady who lies in your arms asleep?”

“Oh, well I like your feather bed, and well I like your sheets.

But better I like your lady gay who lies in my arms asleep.”

“Well, get up, get up,” Lord Darnell cried, “get up as quick as you can!

It’ll never be said in fair England that I slew a naked man.”

“Oh, I can’t get up, I won’t get up, I can’t get up for my life.

For you have two long beaten swords and I not a pocket-knife.”

“Well it’s true I have two beaten swords, and they cost me deep in the purse.

But you will have the better of them and I will have the worse.”

“And you will strike the very first blow, and strike it like a man.

I will strike the very next blow, and I’ll kill you if I can.”

So Matty struck the very first blow, and he hurt Lord Darnell sore.

Lord Darnell struck the very next blow, and Matty struck no more.

And then Lord Darnell he took his wife and he sat her on his knee,

Saying, “Who do you like the best of us, Matty Groves or me?”

And then up spoke his own dear wife, never heard to speak so free.

“I’d rather a kiss from dead Matty’s lips than you and your finery.”

Lord Darnell he jumped up and loudly he did bawl,

He struck his wife right through the heart and pinned her against the wall.

“A grave, a grave!” Lord Darnell cried, “to put these lovers in.

But bury my lady at the top for she was of noble kin.”

Martin Carthy sings Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard

On a day, on a day, on a bright holiday as many there be in the year

When Little Musgrave to the church did go, god’s holy word to hear.

He went and he stood all at the church door; he watched the priest at his mass.

But he had more mind of the fair women than he had of Our Lady’s grace.

For some of them were clad in the green and some were clad in the pall,

And in and come Lord Barnard’s wife, the fairest among them all.

She cast her eye on Little Musgrave, full bright as the summer sun,

And then and thought this Little Musgrave, this lady’s heart I have won.

Says she, “I have loved thee, Little Musgrave, full long and many’s the day.”

“So have I loved, lady fair, yet never a word durst I say.”

“Oh I have a bower at Bucklesfordberry all daintily painted white

And if thou’d went thither, thou Little Musgrave, thou’s lie in my arms all this night.”

Says he, “I thank thee, lady fair, this kindness thou showest to me

And this night will I to Bucklesfordberry, all night for to lay with thee.”

When he heard that, her little foot page all by her foot as he run

He says, “Although I am my lady’s page, yet am I Lord Barnard’s man.

My Lord Barnard shall know of this, whether I do sink or do swim.”

And ever where the bridges were broke, he laid to his breast and he swum.

“Oh sleep thou wake, thou Lord Barnard, as thou art a man of life.

For Little Musgrave is at Bucklesfordberry in bed with thine own wedded wife.”

“Oh if this be true, thou little foot page, this thing that thou tellest to me

Then all my land in Bucklesfordberry freely I give it to thee.

But if this be a lie, thou little foot page, this thing that thou tellest to me

Then from the highest tree in Bucklesfordberry high hanged thou shalt be.”

And he called to him his merry men, all by one by two by three,

Says, “this night must I to Bucklesfordberry, for never had I greater need.”

And he called to him his stable boy, “Go saddle me me milk-white steed.”

And he’s trampled o’er them green mossy banks, till his horse’s hooves did bleed.

And some men whistled, and some men sang, and some these words did say

Whene’er my Lord Barnard’s horn blew, “Away, Musgrave away.”

“Methinks I hear the thistle cock, methinks I hear the jay,

Methinks I hear the Lord Barnard’s horn, and I wish I were away.”

“Lie still, lie still, thou Little Musgrave, come cuddle me from the cold,

For tis nothing but a shepherd boy, adriving his sheep to the fold.

Is not thy hawk sat upon his perch, they steed eats oats and hay,

And thou with a fair maid in thy arms and would’st thou be away.”

With that my Lord Barnard come to the door and he lit upon a stone,

And he’s drawn out three silver keys and he’s opened the doors each one.

And he’s lifted up the green coverlet and he’s lifted up the sheet:

“How now, how now, thou Little Musgrave, dost find my lady sweet?”

“I find her sweet,” says Little Musgrave, “The more tis to my pain

For I would give three hundred pounds, that I was on yonder plain.”

“Rise up, rise up,” thou Little Musgrave, “and put thy clothes on

For never shall they say in my own country i slew a naked man.

Oh I have two swords in one scabbard, full dearly they cost my purse.

And thou shall have the best of them, and I shall have the worst.”

Now the very first blow Little Musgrave struck, he hurt Lord Barnard sore;

But the very first blow Lord Barnard struck, little Musgrave ne’er struck more.

Then up and spoke his lady fair, from the bed whereon she lay,

She says, “Although thou art dead, thou Little Musgrave, yet for thee will I pray.

I will wish well to thy soul, as long as I have life,

Yet will I not for thee Lord Barnard, though I am your own wedded wife.”

Oh he’s cut the paps from off her breast, great pity it was to see

How the drops of this lady’s heart’s blood came a-trickling down her knee.

“Oh woe be to ye, me merry men, all you were ne’er born for my good.

Why did you not offer to stay my hand, when you see me grow so mad?”

“A grave, a grave,” Lord Barnard cried, “to put these lovers in.

But lay my lady on the upper hand, she was the chiefest of her kin.”

Nic Jones sings Little Musgrave

As it fell out upon a day, as many in the year,

Musgrave to the church did go to see fair ladies there.

And some came down in red velvet and some came down in pall,

And the last to come down was the Lady Barnard, the fairest of them all.

And she’s cast a look on the little Musgrave as bright as the summer’s sun.

And then bethought this little Musgrave, this lady’s love I’ve won.

“Good day, good day, you handsome youth, God make you safe and free,

What would you give this day, Musgrave, to lie one night with me?”

“Oh, I dare not for my lands, lady, I dare not for my life,

For the ring on your white finger shows you are Lord Barnard’s wife.”

“Lord Barnard’s to the hunting gone and I hope he’ll never return;

And you shall sleep into his bed and keep his lady warm.”

“There’s nothing for to fear, Musgrave, you nothing have to fear.

I’ll set a page outside the gates to watch till morning clear.”

And woe be to the little footpage and an ill death may he die,

For he’s away to the greenwood as fast as he could fly.

And when he came to the wide water he fell on his belly and swam,

And when he came to the other side he took to his heels and ran.

And when he came to the greenwood, ’twas dark as dark can be,

And he found Lord Barnard and his men a-sleeping ‘neath the trees.

“Rise up, rise up, master,” he said, “Rise up and speak to me.

Your wife’s in bed with the little Musgrave, rise up right speedily.”

“If this be truth you tell to me then gold shall be your fee,

And if it be false you tell to me then hanged you shall be.”

“Go saddle me the black,” he said, “Go saddle me the grey,

And sound you not the horn,” said he, “Lest our coming it would betray.”

Now there was a man in Lord Barnard’s train who loved the little Musgrave,

And he blew his horn both loud and shrill: “Away, Musgrave, away.”

“Oh, I think I hear the morning cock, I think I hear the jay,

I think I hear Lord Barnard’s horn: Away, Musgrave, away.”

“Oh, lie still, lie still, you little Musgrave, and keep me from the cold.

It’s nothing but a shepherd boy driving his flock to the fold.

Is not your hawk upon its perch, your steed has eaten hay,

And you a gay lady in your arms and yet you would away.”

So he’s turned him right and round about and he fell fast asleep,

And when he woke Lord Barnard’s men were standing at his feet.

“And how do you like my bed, Musgrave, and how do you like my sheets?

And how do you like my fair lady that lies in your arms asleep?”

“Oh, it’s well I like your bed,” he said, “And well I like your sheets,

And better I like your fair lady that lies in me arms asleep.”

“Well get up, get up, young man,” he said, “Get up as swift you can,

For it never will be said in my country I slew an unarmed man.

I have two swords in one scabbard, full dear they cost me purse,

And you shall have the best of them and I shall have the worse.”

And so slowly, so slowly, he rose up and slowly he put on,

And slowly down the stairs he goes a-thinking to be slain.

The first stroke little Musgrave took it was both deep and sore,

And down he fell at Barnard’s feet and word he never spoke more.

“And how do you like his cheeks, lady, and how do you like his chin?

And how do you like his fair body now there’s no life within?”

“Oh, it’s well I like his cheeks,” she said, “And well I like his chin.

And better I like his fair body than all your kith and kin.”

And he’s taken up his long, long sword to strike a mortal blow,

And through and through the lady’s heart the cold steel it did go.

As it fell out upon a day, as many in the year,

Musgrave to the church did go to see fair ladies there.

Acknowledgements

Transcribed from the singing of Martin Carthy by Garry Gillard.

Performances, Workshops, Resources & Recordings

The American Folk Experience is dedicated to collecting and curating the most enduring songs from our musical heritage. Every performance and workshop is a celebration and exploration of the timeless songs and stories that have shaped and formed the musical history of America. John Fitzsimmons has been singing and performing these gems of the past for the past forty years, and he brings a folksy warmth, humor and massive repertoire of songs to any occasion.

Festivals & Celebrations Coffeehouses School Assemblies Library Presentations Songwriting Workshops Artist in Residence House Concerts Pub Singing Irish & Celtic Performances Poetry Readings Campfires Music Lessons Senior Centers Voiceovers & Recording

““Beneath the friendly charisma is the heart of a purist gently leading us from the songs of our lives to the timeless traditional songs he knows so well…”

Join Fitz at The Colonial Inn

“The Nobel Laureate of New England Pub Music…”

On the Green, in Concord, MA Every Thursday Night for over thirty years…

“A Song Singing, Word Slinging, Story Swapping, Ballad Mongering, Folksinger, Teacher, & Poet…”

Fitz’s Recordings

& Writings

Songs, poems, essays, reflections and ramblings of a folksinger, traveler, teacher, poet and thinker…

Download for free from the iTunes Bookstore

“A Master of Folk…”

Fitz’s now classic recording of original songs and poetry…

Download from the iTunes Music Store

“A Masterful weaver of song whose deep, resonant voice rivals the best of his genre…”

“2003: Best Children’s Music Recording of the Year…”

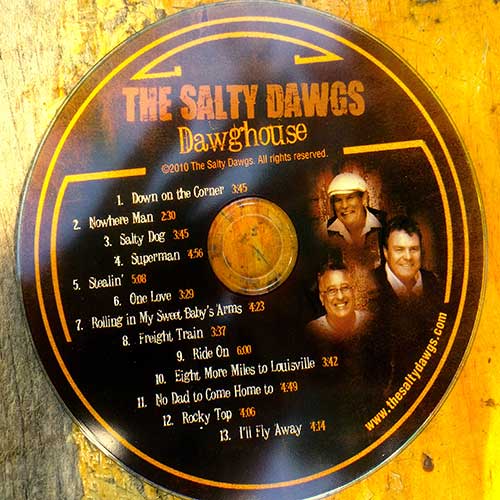

Fitz & The Salty Dawgs Amazing music, good times and good friends…

0 Comments